Corporate Value

Business strategy is concerned with how much a specific business can create value. In corporate strategy the central question is ”How can you tell if your company is really more than the sum of its parts?”. i.e. Are the benefits of corporate membership greater than its costs ?

Corporate strategy should be guided by the vision of how a firm, as a whole, creates value. In any multi-business company, an efficient corporate strategy can contribute to value creation. Conversely a less efficient corporate strategy can destroy value.

This section borrows from ( [Collis98] )

Corporate Advantage

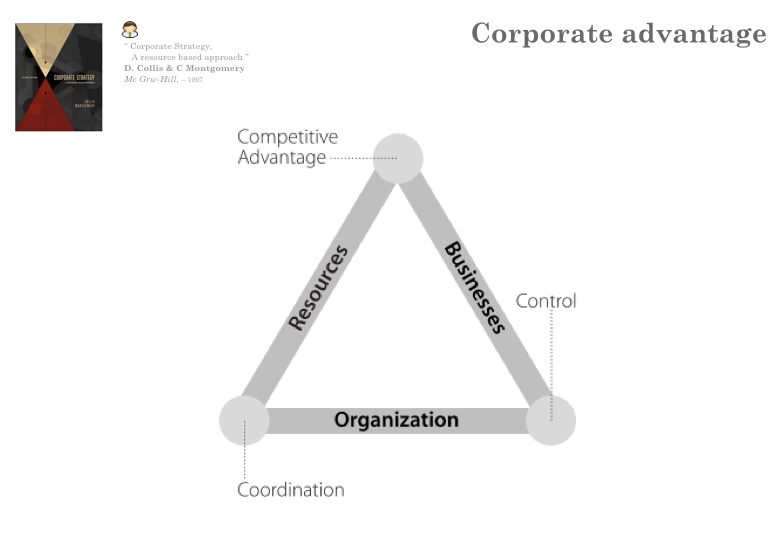

According to Collis and Montgomery, creating viable corporate strategies requires combining three major ingredients: resource, business and organization.

In other words, it requires working on core competence, restructuring the corporate portfolios and building organizations. Besides, turning those elements into an integrated whole is the true essence of any corporate advantage.

A successful corporate strategy must therefore be a constructed system of three interdependent parts. When a company owns the resources that are critical to the success of its businesses, it possesses a competitive advantage. When the organization is configured to leverage those resources into the businesses, synergy can be captured and coordination achieved. Finally, a good fit between a company’s measurement & reward systems and its business logics allows strategic control.

Resource Continuum

The firm’s resources define the businesses that make sense for it to own and those that don’t. The resources that provide the basis for corporate advantage range along a continuum, from the highly specialized (e.g. technology specific) to the very general (e.g. management skills, corporate governance).

Firms with specialized resources will usually compete in a narrower range of businesses (where the resources are relevant and can deliver a competitive ad- vantage) whereas firms relying upon more general resources can own a large variety of businesses

The type of resources also defines the most appropriate mode of coordination, from sharing (e.g. common sale force) to transferring (which preserves the autonomy and accountability of the business units).

Relatedness trap Managers often fail to recognize that it is about resources and not about product. In their article, Collins & Montgomery give the example of industrial thermostats that require re- sources such as strong R&D capabilities, expertise in strict tolerance, made-to-order production capabilities, a technically sophisticated sale force. By contrast, in household thermostats the resource expected to be competitive are : product design & appearance, packaging, mass production, distribution through mass marketers & retailers. As a consequence, a firm that is successful in industrial thermostats is unlikely to also succeed o household thermostats. Indeed, although it could leverage some of its knowhow and competences, it would not use many of the factors from industrial thermostats and would lake most of the factors to compete in household thermostats.

Coordination mechanism Corporate strategy seeks to deploy the resources that are key to each individual business. Resources can be either shared among several businesses or transferred across businesses with a minimum of coordination (at arm’s length).

Public Goods (e.g. brand name, best practice) are easy to transfer, as they are non-excludable and non-rivalrous (the use by one business doesn’t reduce the availability for the others). Each business will seek to develop & capitalize on these valuable resources. However it may be necessary to ensure that the com- pany continue to invest in these resources and also to prevent from the re- source to loose value and/or get spoiled by one business.

Private goods by contrast, correspond to resources that are used by several business units (e.g. sale force, MIS, join procurement, factory). A private good can be transferred to a specific business or kept at corporate level and shared across several businesses. It usually requires a lot of coordination to reach consensus on the specifications of a shared resource and to reach a compromise agreement.

Control system

The corporate centre highly relies on its control system to steer the divisions toward the chosen strategic direction and influence performance in the individual businesses. Choices about what to measure and what to reward are therefore absolutely key.

By and large control systems are of two types: operating or financial. Financial control holds managers accountable for a limited number of objectives that are measurable (sale growth, return on assets). By contrast operating control aims at appraising managers’ decisions and actions (including when facing unexpected events).

While most companies tend to use a mix of the two, successful corporate strategies emphasize one or the other, subject to the nature of the business in the portfolio and the relative expertise of corporate executives. Financial control is more appropriate in mature and stable industries while in fast moving industries with high levels of uncertainty, operating control is more appropriate.

Parenting Advantage

According to Alexander, Campbell and Goold ( [Campbell95] ) the core question in corporate strategy is whether or not the corporate brings value to the businesses it owns.

A parent company (corporate) sits between the shareholders and the various businesses it owns. As such, it reduces the leeway of both the shareholders and the businesses and induces additional costs. A multi business parent creates value (for the shareholders) if the various businesses perform better in aggregate than they would as a series of individual stand-alone entities. In addition, parents should strive to create more value out of their portfolio than could be achieved by any rival (other parent company, investment fund, shareholders).

Corporate strategy triggers two major decisions:

Parent’s characteristics how the parent should influence its business ? ”what organizational structure, management processes, and philosophy will foster superior performance from its businesses ?” Successful parents focus on a small and internally consistent set of insights that enable them to become the specialists : they are clear about their own roles.

Portfolio What businesses should this company, rather than rival companies, own and why ? What should be added, split off or sold ? To optimize value, the parent must select the businesses so that there is a fit between the parent’s characteristics and the most significant business improvement opportunities.

Alexander, Campbell and Goold have coined parenting advantage the ability of a parent to create value. They consider that two conditions are necessary for a parent to provide value to its businesses: i) the corporate executives must deeply understand and feel the business of their businesses and ii) the parent must have some competences or resources that is specially helpful to its business (there must be room for improvement and the parent must be helpful). Moreover they stressed that “the fit between parent and businesses is a two-edged sword: a good fit can create additional value; a bad one can destroy value”.

According to them, there are several sources of value destruction:

Standalone influence parents are involved in “agreeing and monitoring performance targets in approving major capital expenditures and in selecting the business unit managing directors”. However, parents often also interfere more deeply in product policy, marketing or human resources matters. The authors illustrate the bad influence of parents with the example of oil companies that all sought to diversify into minerals arguing that they mastered the skills and competences in natural resource exploration and extraction. There are however, many subtle differences between the oil business and the minerals and despite similarities, the two businesses relies on very different critical success factors. Corporate executives - all oil business veterans - pushed their mineral units to make poor (or sometimes bad) decisions. “The corporate executives couldn’t really get to grips with the mineral business, they couldn’t feel it”. After ten years of unsuccessful experience, oil companies have divested their minerals businesses. Usually the executive running the business are better informed / knowledgeable about their business than the parent executives.

Linkage influence a corporate parent may seek to foster synergies across its various business. More often than not, the costs of establishing common systems and services out weight the benefit of sharing. Global processes (e.g. cross selling) require additional layers of coordinations and the overhead costs are not always compensated by additional sales.

Central Function & Services establishing central services (common to several or all the units and managed centrally by the head quarter) usually implies increasing overhead costs, increasing response time and the deterioration of the quality of service as the function gets more remote from the business.

Corporate development Research indicates that the majority of Corporately sponsored acquisitions, alliances, new ventures and business redefinitions fail to create value.

Assessing the parenting first

Assessing the fit between a parent company and its businesses is a critical but tough question. Alexander, Campell and Goold suggest that it should encompass the following steps:

Understanding the critical success factors for each and every business owned by the parent: what does it take to be successful ? Each industry relies on a few activities or issues that are critical to performance. Furthermore a specific business may derive a competitive advantage (firm specific advantage) from a few characteristics. A parent can create value to a set of apparently non-related business, provided that the critical success factors are not too dissimilar.

Identify potential upsides the parent can only create value in businesses where there is room for improvement. It is therefore crucial to identify areas of improvement (potential parenting opportunities). Several sources of parenting opportunities are underlines in [Campbell et al., 1995b] : killing bureaucracy, providing financial resources, attracting and retaining top managers, improving marketing, streamlining production, economies of scale, shared and scarce expertise, lobbying and external relationships, etc. Most business could improve their performance if they had the parent with the adequate skills and abilities.

Delineate the characteristics of the parent in this step, the focus is on the capacities of the parent. What expertise, specific capabilities, differentiating skills can the parent bring to its businesses. According to [Campbell et al., 1995b] several characteristics must be taken into account. The parent’s mental maps encompass to the (often implicit) value of the parent, its biases, simplification principles and rules of thumb. The capability of a parent to truly understand and feel a specific business, often derives from its mental maps. The parenting structures, systems and processes correspond to the mechanisms the parent usually deploy to create value. It includes the management structure and layers, the appointment principles, budgeting planning and investment approval system, governance and decision-making structures, etc. The corporate structure (specific staffs, departments at the headquarter, central functions and expertise) is also a key ingredient of parenting value creation. Last but not least the centralization / decentralization balance between the parent and its business defines the nature and perimeter of the influence the parent needs to have on its businesses.

Fit between the parent characteristics and the potential upsides once both the potential upsides and the characteristics of the parent have been revealed, it gets easier to appraise how much the parent can bring or conversely how penalizing its influence can be. The parent that owns the proper characteristics (resources, skills, knowhow, behavior) can exploit the upside potential of the businesses. By contrast, if the parent characteristics don’t fit with the business critical success factor, there is downside in the relationship with the business.

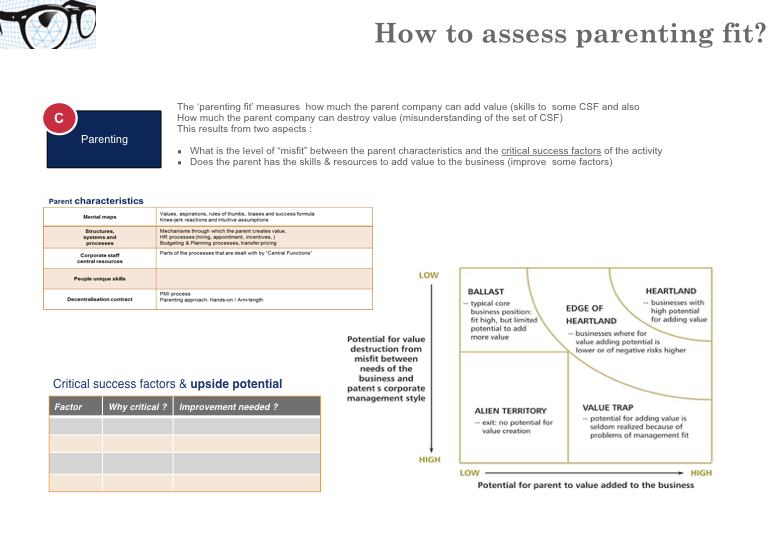

The parenting Matrix

The parenting matrix is built along two axes: i) how well the parent fits the business upside opportunities and ii) how well the parent characteristics fits critical success factors of the business. In other words, how much the parent can help the business and how much it understands and feels the business.

Heartland businesses correspond to businesses where the parent both can improve the performance and deeply understand the critical success factors. Ideally, all the businesses in a group should be “heartland” businesses.

Edge of Heartland some parenting characteristics fit but not all. Value creation is partly offset by elements that fit less and can destroy value (at least lack value creation potential). The net contribution to value is not clear-cut.

Ballast businesses the parent understands the business extremely well and is very comfortable with the business. The parent doesn’t have howe- ver the right characteristics to help the business improve its performance. A more adequate parent would create more value. In addition, there is a danger that a change in the business environment can move a ballast business into an alien-territory business.

Alien-Territory businesses correspond to businesses for which the pa- rent can’t help improve performance and in addition, the parent characteristics don’t fit with the critical success factors. This is the typical area where the parent destroy value.

Value Trap businesses this is the areas where parent executives have the worst influence and make the biggest mistakes. They are business with a fit in parenting opportunity and a misfit in critical success factors. Businesses in this area can receive positive support from their parent company. However the parent executive fail to truly understand the business environment and priority. “The potential for upside gains blinds managers to downside risks”.

Parenting Value Adding & Destroying

Typical value adding capabilities that can be brought by a parent company include:

Envisioning clear overall vision and strategic intend for its business units

Coaching assist BU managers in developing strategic capabilities, facilitate sharing among units. Corporate-wide training is usually one of the effective means to foster cooperation among BUs.

Providing Central Service - either centralize capital investment and/or provide shared services such as HR, Legal, Communication, Information Services.

Intervening closely monitor performance of the BUs and assist or re- place weak managers when performance doesn’t meet the targets.

There are also circumstances where a parent destroys value:

Adding overhead Costs staff& facilities of the corporate centre(i.e.HQ) can be expensive while not producing any revenues.

Adding bureaucratic complexity reporting, additional management layers Averaging effect - when monitoring isn’t robust enough or transparent, weak under-performing businesses can survive longer.

Types of Corporate Parenting roles

There are three main archetypes of parenting role.

The portfolio manager is acting as an “agent” on behalf of the financial mar- kets. Such a parent company doesn’t get closely involved in the routine management of the various businesses, except over short period of time to improve performance. The parent company concentrate on providing (respectively withdrawing) capital investments. The CEOs of the BUs enjoy a high degree of autonomy but are given clear performance targets (with high reward in case targets are met and the risk to loose their position otherwise). The parent company periodically make evaluation about the well-being and future prospect of the businesses and review its investing/divesting schemes accordingly.

The synergy manager is a parent company seeking to generate value by in- creasing synergies among its BUs. It heavily relies on envisioning to create a common purpose. It also facilitate and foster cooperation among BUs. More often than not the parent company will seek to provide shared services to in- crease as much as feasible synergies. There is the risk of illusory synergies (i.e. synergies that are claimed but never materialize).

The parental developer is a parent company that seeks to leverage its own central capabilities to add value to its businesses. It typically focuses on resources it owns as a parent and on how to transfer downward to BUs (rather than on how to foster synergies across BUs).