What Return ?

Some general managers tend to believe that maximizing revenue growth and maximizing profit would be the holy grail of management. However, they are making a major flaw in ignoring the level of investment that was required to obtain that profit

According to Paul Barnett, it is Milton Friedman (one of the most influential economist, from the Chicago School, who received the Nobel Prize in Economic Science in 1976) who imposed maximizing shareholder value as the sole purpose of a firm. Putting shareholder value at the forefront is now being challenged by both academics and practitioners.

A firm must create value and capture some. More precisely it must capture value in excess of the opportunity costs of its financing. Generating profit is not good enough. Profit must be considered in comparison to the level of capital (equity and debts) it requires to get generated. Profit must be compared to the level of investment that was required. This section explores various ratios used to evaluate the return.

What is Profit ?

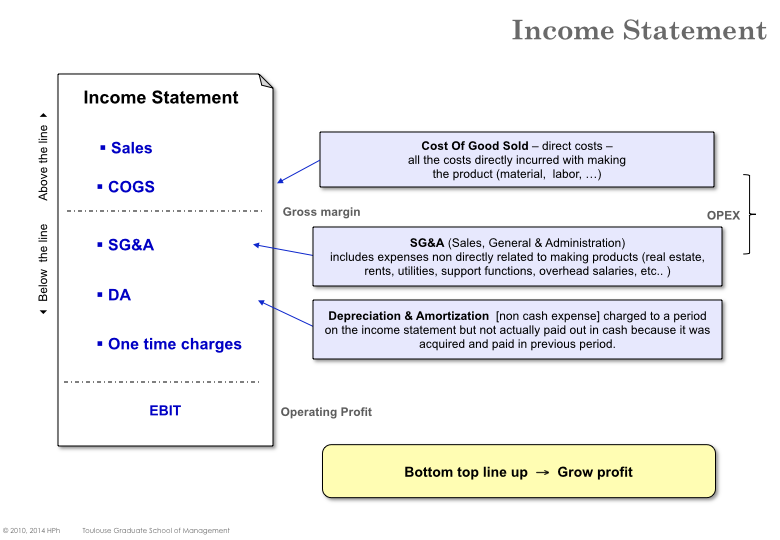

Income Statement

The income statement (also called the Profit and Lost or P&L statement) reports revenues and expenses for a fiscal period. It represents flows that is the summary of what happened during a period (quarter, year).

The Gross Margin is obtained by subtracting the cost of good sold from revenue. The Cost of Goods Sold (COGS also called Cost of Sales) corresponds to expenses directly attached to producing the product or delivering the service (e.g. Raw material, Wages and salaries, Packaging, Energy & consumables for the machinery, …).

The EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) is obtained by subtracting SG&A (Marketing & Sales, Administration, R&D – sometimes called overhead or non-productive costs)costs and one-off costs (if any) from the gross margin. The EBITDA reflects both direct and indirect costs and is a cash flow item (the sum of cash actually received or spent).

The Operating Profit or EBIT is obtained by subtracting Depreciation and Amortization from the EBITDA. Depreciation and Amortization refer to the decrease in value of assets that are used during several periods (e.g. plants, buildings, machinery, …). DA doesn’t correspond to any actual payment (payment took place in the past when the asset was acquired). Therefore the EBIT is not a cash item.

For the purpose of preparing an Income Statement, revenues and expenses are not accounted exactly when money transfer occurs: i) Sales are accounted when the product or service is delivered – the actual payment will usually happen later and ii) Expenses are as well accounted when the product is delivered. The P&L doesn’t reflect all the events that altered the financial position (equity increase, bond issue, inventory, etc).

Note: Strictly speaking EBIT and operating profit are two different things in the sense that EBIT may encompass non-operating income as well. However, more often than not, EBIT and opera- ting profit are considered equivalent.

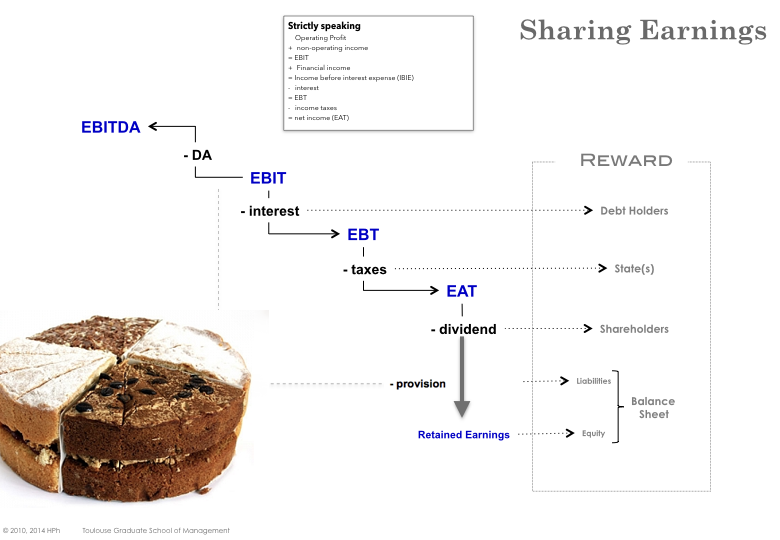

Sharing earnings

The operating profit – which can be seen as the result of operating the business – cannot be kept entirely by the firm. Indeed several stakeholders claim there share of pie.

What remains (positive or negative number) once interests and taxes have been paid, is named the net income (aka Earnings After Taxes). A part can be paid to the shareholders as dividend and the remaining (retained earnings) is kept by the company (adds up to the equity part in the balance sheet).

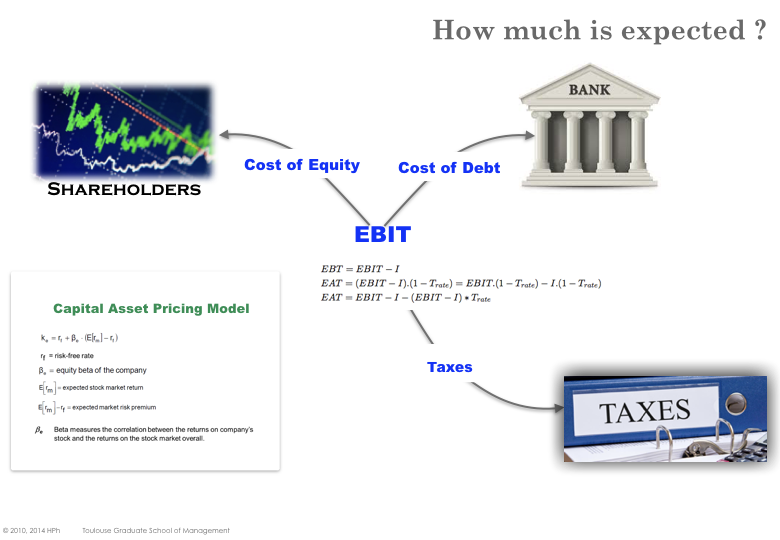

Cost of Capital

The various stakeholders form expectations about the return they might receive from the firm.

Taxes

Tax authorities are relatively clear about what they expect. The word ’clear’ is arguably not suitable here as tax law can be very complex and obscure. However taxes are due and are rather deterministic.

Debts

In exchange for the money that they lend, debt holders expect to receive compensation (typically an interest rate). From the perspective of the firm this is cal- led the cost of debt.

Shareholders

Shareholders also expect a return from their investment. However (and unlike the tax authorities and debt holders) shareholders bear more risks and are associated to the fate of the business.

The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is one of the most famous theoretical model that assess the appropriate rate of return of an asset. By and large it considers that the expected return for any business should be the risk-free return (typically treasury bond) to which a premium is added, subject to the level of risk of the business.

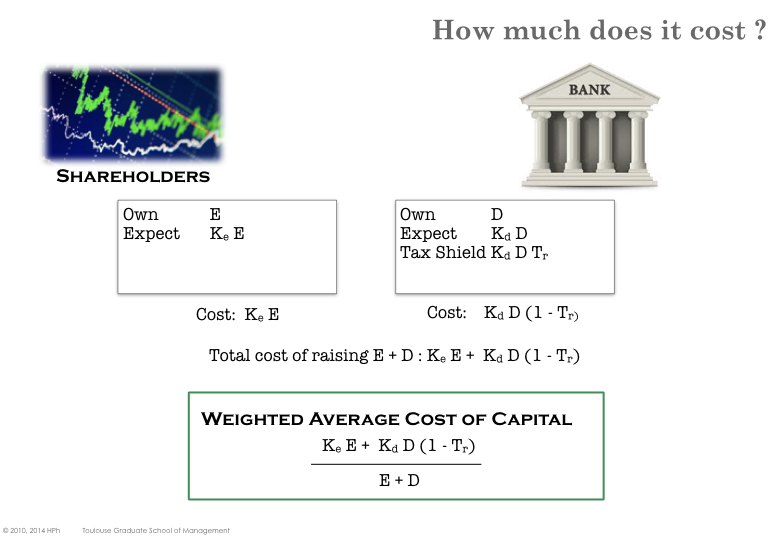

Weighted Average Cost of Capital

Excluding current liabilities, a firm receives its capital from its shareholders who own the equity (E) and debt holders who own Long-term debts (D).

Shareholders expect \( K_e \) in return for their investment, which for the firm, corresponds to a total cost of equity of \( Ke.E \). Likewise, debt holders expect \( K_d \), which for the firm, corresponds to a total cost of debt of \( Kd.D \). The total cost of raising \( E + D \) is therefore \( Ke.E + Kd.D \). The average cost, named the WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital), of raising one unit (i.e. one euro, one dollar, etc…) is therefore: \( \frac{Ke.E+Kd.D}{E+D} \)