What does 'Strategy' mean ?

“Strategy” in everyday’s conversations

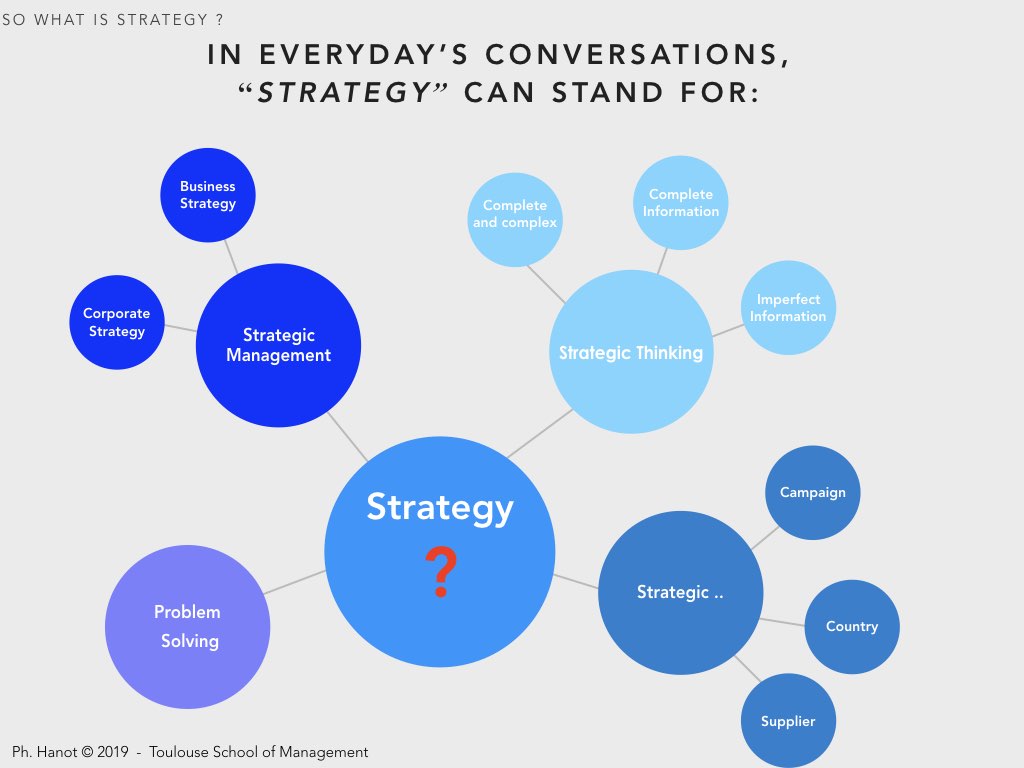

In everyday conversations the word strategy far exceeds the domain of strategic management. Considering just a glimpse of the many different meanings, at least three specific contexts can be stressed, in addition to strategic management: strategic thinking, problem solving and important things.

'Strategy' goes beyond Strategic Management '

Strategy for Important

It is very common to hear about strategic customers, strategic suppliers, strategic country, strategic campaign, strategic project, etc. More often than not, the adjective strategic stands here for ‘important’ and unless evidence of scarcity, uncertainty or decision can be found, such situations have only very remote resemblance with strategic management.

For instance strategic customer must be understood as important customer, except maybe if that customer is an opinion leader for the industry that can influence other customers.

Strategy for Problem Solving

The word strategy is also commonly used to mean way to solve a problem (i.e. Strategy as a plan or what behavioral scientists and computer scientists call a heuristic).

'Strategy' for Problem solving '

In the above example Strategies for organizing items in the garage sounds great but must be a bit remote from strategic management.

Strategy for Strategic Thinking

'Strategy' for Strategic Thinking '

Strategic Thinking, a Primer

The notion of strategic interaction is one of the core concepts for strategic thinking.

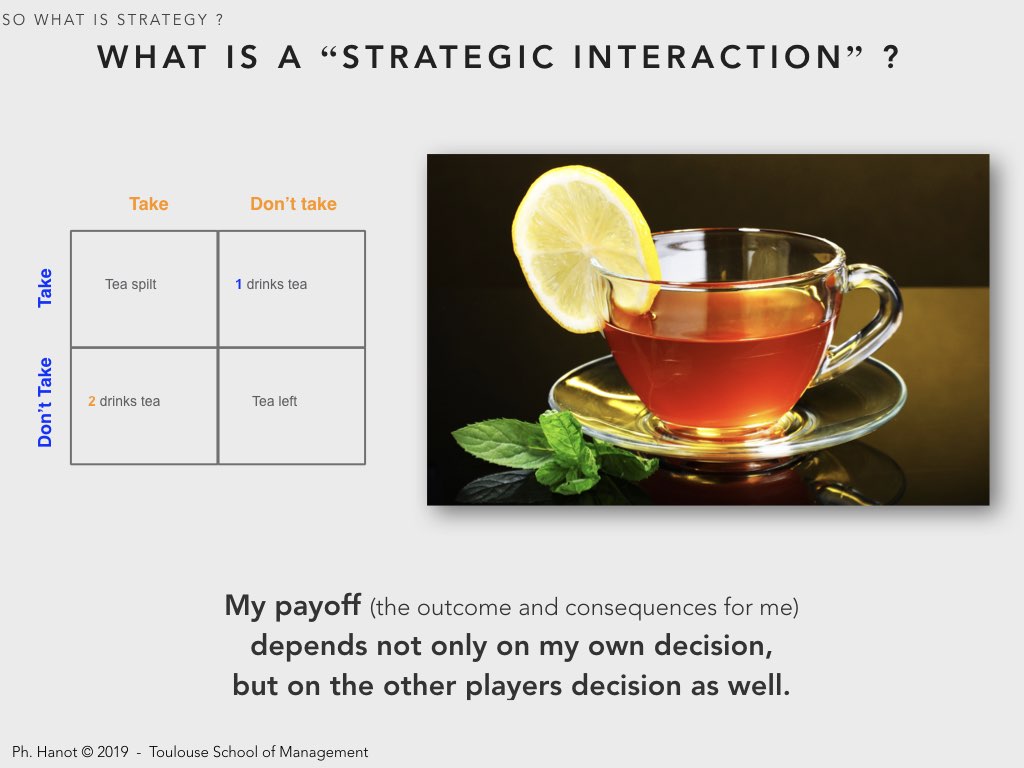

'Strategic Interaction'

Let’s assume there is a buffet and we all rush to the refreshments. As a consequence when the last two persons arrive there is only one cup of tea left. These two persons both have two options: either take or don’t take the tea. This can be represented by a table or matrix, where rows correspond to one person’s actions and columns to the other’s.

If they both take the tea it is likely to spill and will be lost for both, if neither take the cup, the tea will be left. Otherwise one person will drink the tea.

What is key here is that the outcome for each person (his or her payoff) not only depends upon her/his own decision but as well on the other person’s decision.

Likewise it is important to note that if there were many cups of teas, this would no longer be a strategic interaction because whether or not one of the person takes a cup of tea, would barely have any impact on the ability of the other person to have a tea.

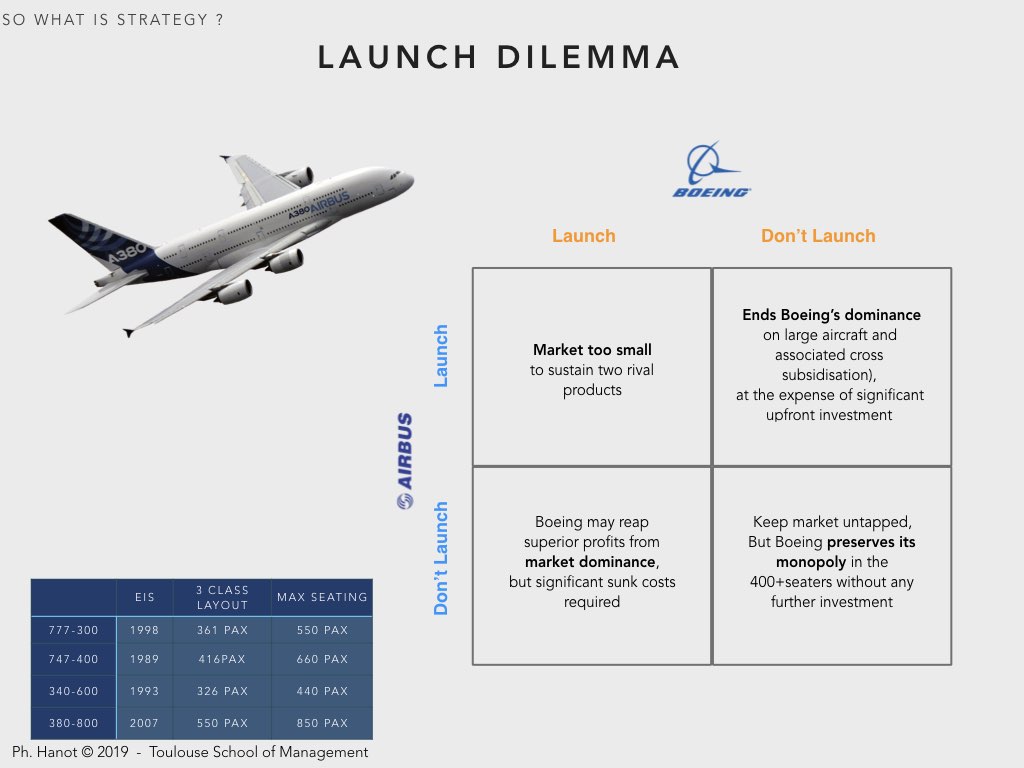

The launch dilemma

The previous example may look “toyish”, nevertheless it can apply to many real life business situations.

'The launch dilemma'

We’re in the late 90s, both Airbus and Boeing have worked on Very Large Aircraft projects, they even contributed to a joint feasibility study but it became obvious that Boeing was playing for time.Airbus had announced its plan to develop its own aircraft, coined A3XX. The two players have the same two options: launch or don’t launch a Large Aircraft.

The two players acknowledge that the market is too small to sustain two products and therefore none of the player would breakeven their investments if both would launch. If none decide to launch the ‘Very Large Aircraft’ market remains untapped, however the situation is asymmetric as Boeing already dominate the 400+ seater market with the 747. Therefore Boeing has more interest than Airbus to maintain the status quo.

We know how it ended up: Airbus launched the A380 and terminated Boeing’s dominance on the upper segment. As a result Boeing is phasing out its 747.

Learning Point

We all know we should Put ourselves in everybody else’s shoes but sometimes we tend to overlook some beliefs or consider that the situation is completely symmetrical where it is not.

'Not all situations are symmetrical'

Likewise, the level of strategic interaction varies for a given interaction type.

For a given interaction type, the level of interaction may vary

The more you are able to consider a situation from the perspective of the other stakeholders, the better you can anticipate and make an educated decision.

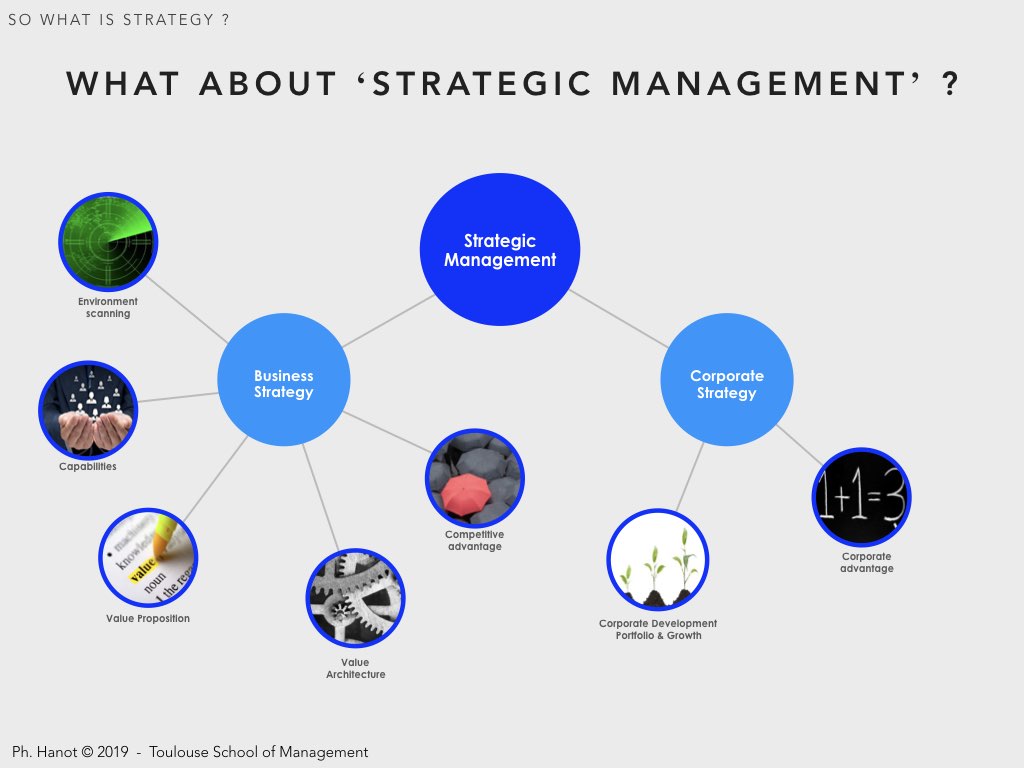

What about ‘Strategic Management’ ?

Strategic Management encompasses Business Strategy and Corporate Strategy

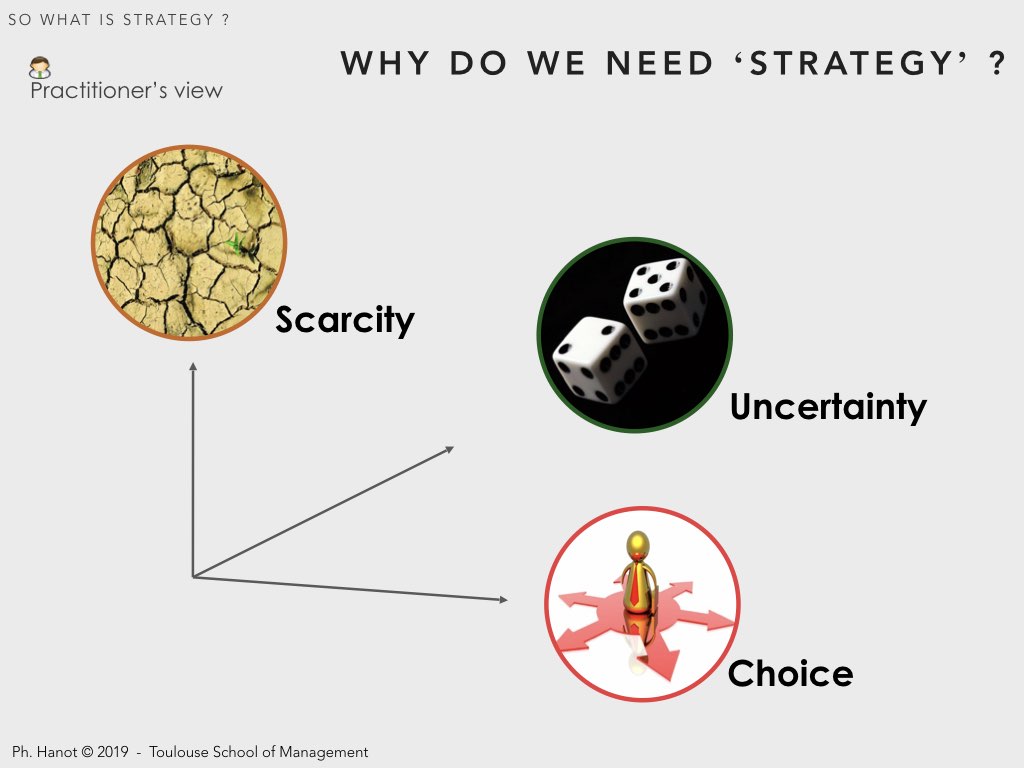

Why do we need Strategy ?

Even before trying to define WHAT strategy is (at that stage let’s consider that strategy conveys the idea of being successful ), we may wonder WHY do we need strategy at all?

Three main factors are underpinning Strategy.

By and large, three major factors underpin the need for strategy :

Scarcity – without limitation (of resources, skills, demand, competence, time, …) there would be no competition, no struggle to succeed, to control and access knowhow, markets or supply chains. Without scarcity all players could be equally successful, without effort

Uncertainty – firms are exposed to dynamic ecosystems (customers, suppliers, competitors, society, authorities). Things change, often unpredictably. Risk is also inherent to most strategic moves and success can never be taken for granted. In addition, when a player initiates a strategic move, the actual outcome usually also depends upon other players’ reaction, which is rarely easy to forecast. Conversely, existing or to-be competitors may also make anticipated moves, which usually trigger chain responses.

Choice – firms have to make decisions about their long-term orientations. It is usually important to explore several options, probing each one carefully before making a choice. But it is even more important to do make a choice. A firm has no real strategy until it has crossed the Rubicon and made irreversible decisions: select their perimeter of activities (what to do and what not to do), their operating model (how to do it) while preparing their future (e.g. innovation).

A situation where no limitation can be spotted, everything seems deterministically planned and no specific decision is expected, should be considered with care. It may be the sign that it does not fall within the scope of strategic management, or that it requires some serious reassessment.

« A real strategy involves a clear set of choices that define what the firm is going to do and what it’s not going to do. Many strategies fail to get implemented, despite the ample efforts of hard-working people, because they do not represent a set of clear choices. Many so-called strategies are in fact goals. We want to be the number one or number two in all the markets in which we operate is one of those. It does not tell you what you are going to do; all it does is tell you what you hope the outcome will be. But you’ll still need a strategy to achieve it.» ( [Vermeulen] )

The 5 P for Strategy

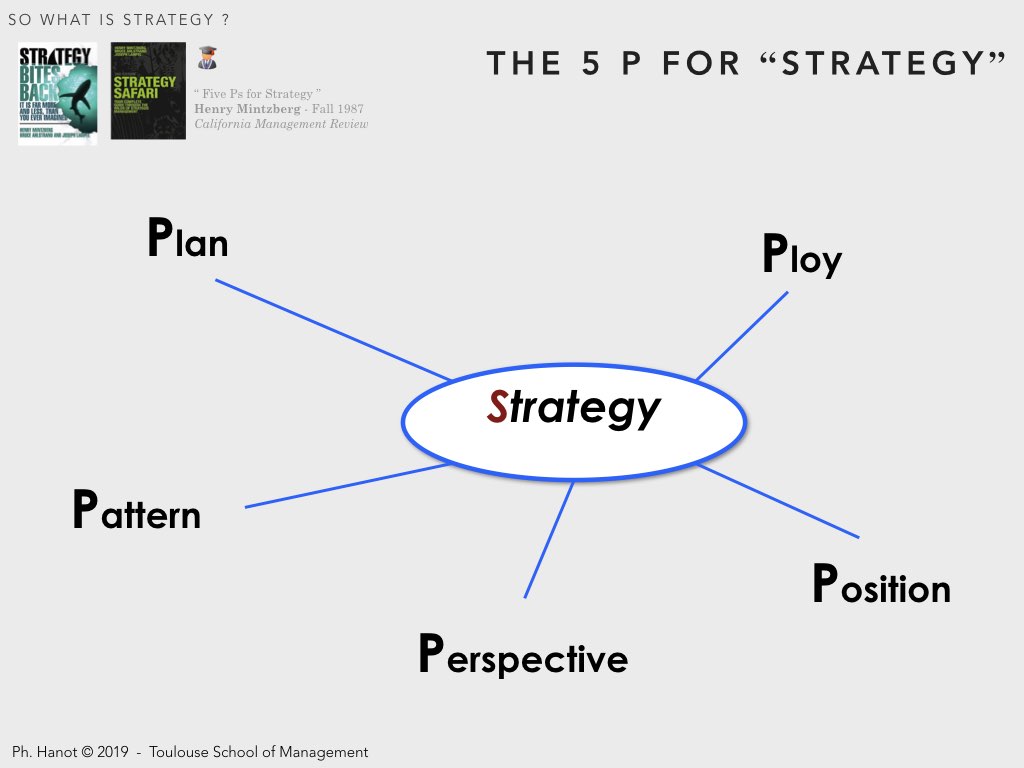

In a seminal work, Henry Mintzberg ( [Mintzberg87] [Mintzberg98] [Mintzberg05] ) stresses that the word strategy is being used in five different ways, in the field of strategic management, even if it is traditionally defined formally only in one.

The word ’strategy’ encompasses at least five different meanings.

Strategy as a Plan

Considered as a plan, strategy is some sort of consciously intended course of action, a guideline (or set of guidelines) to deal with a situation. By this definition, plans have two essential characteristics: they are made in advance of the actions to which they apply and are developed purposefully.

As a plan, a strategy is formulated through a conscious process and can be stated explicitly and formally. To Drucker ( [Druker85] ) strategy is purposeful action.

In Game Theory ( [VNM44] [Polak07] [Dixit15] [Aumann92] ) Strategy is a complete ‘algorithm’ for playing the game. A Strategy tells a player what to do for every possible situation throughout the game.

Strategy as a Ploy

‘Strategy’ can as well correspond to a specific maneuver intended to outwit an opponent. A firm may pretend to establish a new practice area to discourage a competitor to do so. Here the real strategy (the real intention) is to prevent the move from the competitors and not the new practice area itself.

Strategy as Pattern

A strategy will be considered to have formed when as sequence of decisions exhibit some consistency over time. While strategy as a plan and/or a ploy are always indented, strategy as a pattern is not necessarily planned neither foreseen in advance.

Strategy as a pattern – i.e. a stream of actions, consistency in behavior – can be compared to periods of great artists (i.e. their decisions about their work), where certain consistencies in their use of colors, forms, etc. can be observed (e.g. Picasso’s blue period). Strategy, in that case, corresponds to a posteriori consistencies in decisional behavior (whether intended or not).

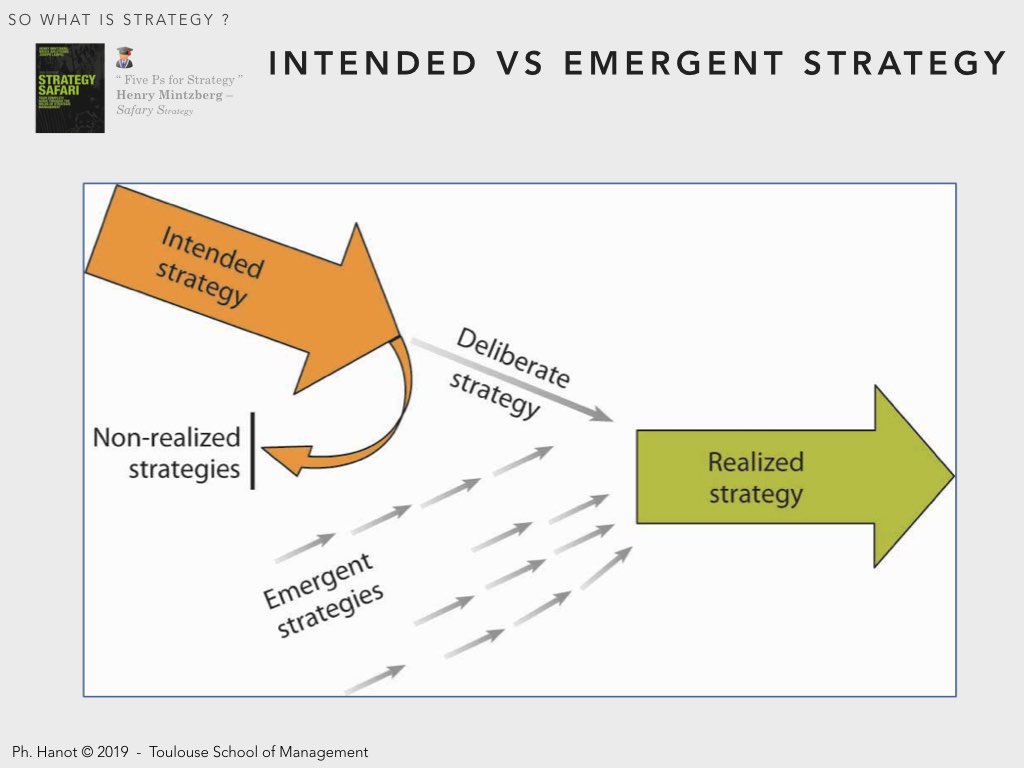

Intended vs emerging strategy

The definitions of strategy as plan and pattern can be quite independent of one another: plans may go unrealized, while patterns may appear without preconception. A strategy-maker may formulate a strategy through a conscious process before he makes specific decisions, or a strategy may form gradually, perhaps unintentionally, as he makes his decisions one by one.

In other words, strategies are not always deliberately planned.

As stressed by the Open University ( [OpenU] ) “ every time a journalist imputes a strategy to a corporation or to a government, and every time a manager does the same thing to a competitor or even to the senior management of his own firm, they are implicitly defining strategy as pattern in action – that is, inferring consistency in behavior and labelling it strategy. They may, of course, go further and impute intention to that consistency – that is, assume there is a plan behind the pattern. But that is an assumption, which may prove false ”.

Strategy as Position

Strategy can consist in a position, i.e. a match (sometime mismatched) between the internal organization and its external environment.

In management terms, strategy becomes a product-market domain where resources are concentrated. Strategy as a position is what a firm do or don’t do (which is different from the plan, i.e. the course of actions to achieve it). A position can be preselected and aspired to through a plan (or ploy) and/or it can be reached, perhaps even found, through a pattern of behavior.

In economic terms a position generates a rent (returns for being in a unique place). “Strategy is creating situations for economic rents and finding ways to sustain them” ( [Rumelt82] )

Strategy as position must not be limited to ’two-person games’ (head-on competition), or even n-person situations. Strategy as position applies to any viable position, whether or not directly competitive.

Strategy as Perspective

Strategy can be a perspective, its content consisting not just of a chosen position, but also of an ingrained way of perceiving the world that usually echo the deepest firm’s beliefs and values. Some organizations are aggressive pacesetters, creating new technologies and exploiting new markets, other perceive the world as set and stable, sit back in long established markets and build protective shells around themselves, relying more on political influence than economic efficiency. There are organizations that favor marketing and build a whole ideology around that (e.g. IBM) others treat engineering in this way (e.g. Hewlett Packard) and then there are those that concentrate on sheer productive efficiency (e.g. MacDonald’s).

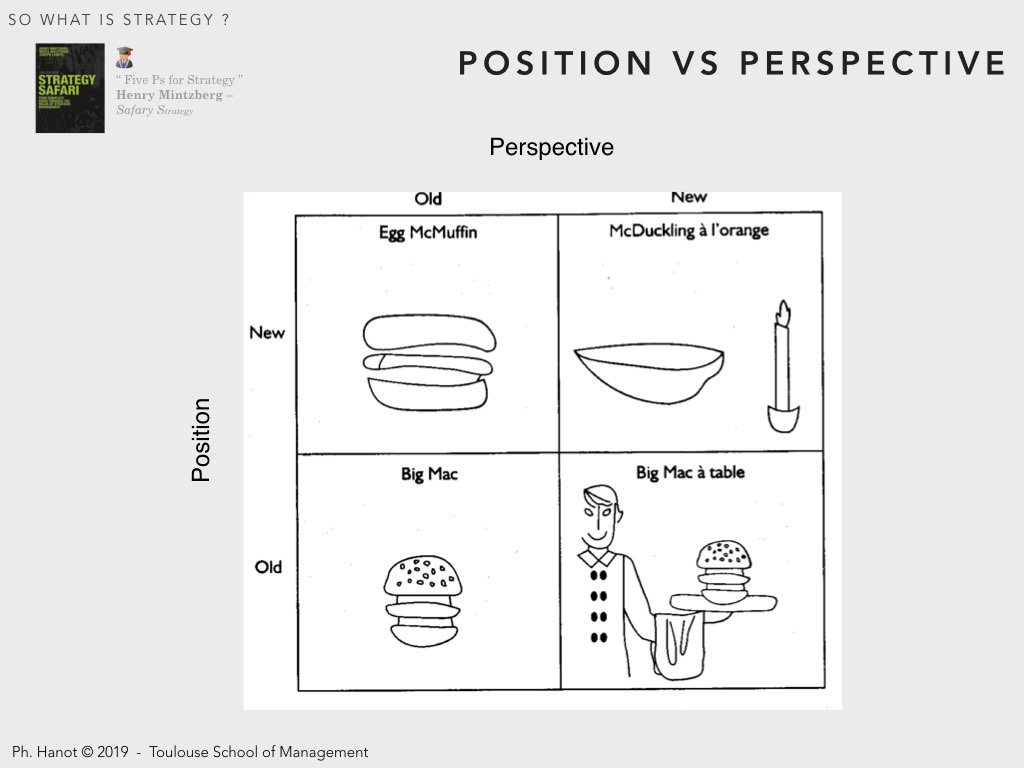

Changing position & perspective.

The above example, borrowed from ( [Mintzberg98] ) illustrates the difference and complementarity between strategy as a position and strategy as a perspective. McDonalds can focus on hamburger for lunch and diner or diversify into sandwitches for breakfast (they did in the late 90’s). However, McDonalds can continue to see itself as a fast food and value speed or want to conceive itself as a more sophisticated restaurant (with tablecloth / candles / china and silver cutlery).

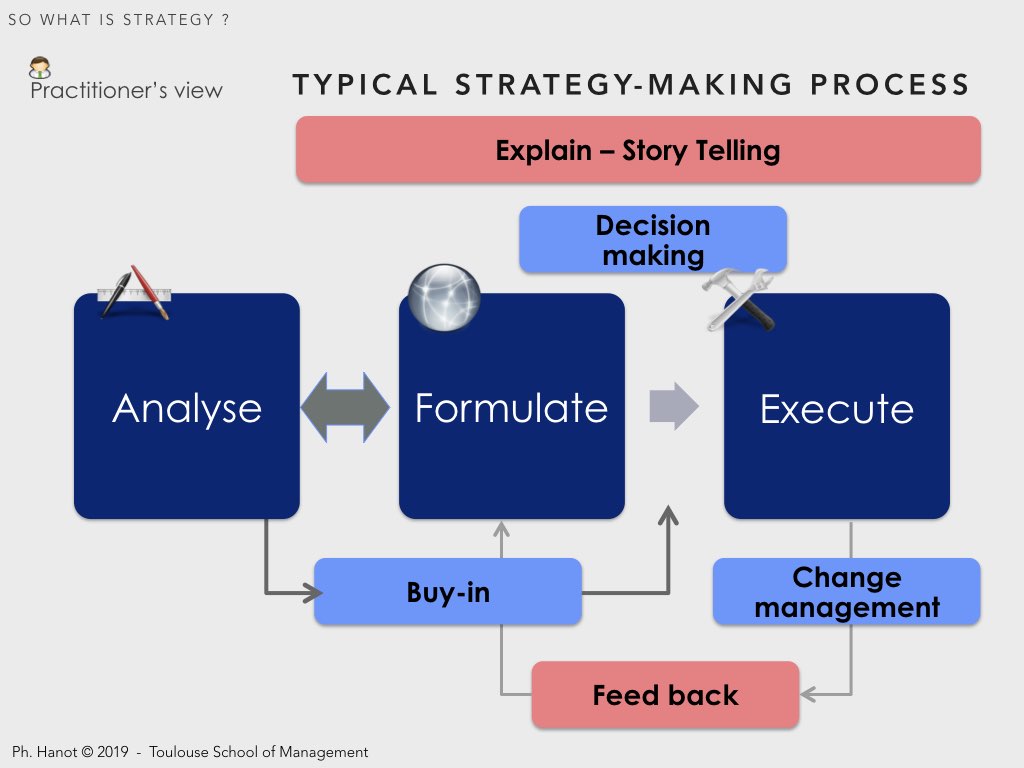

Strategy Making Process

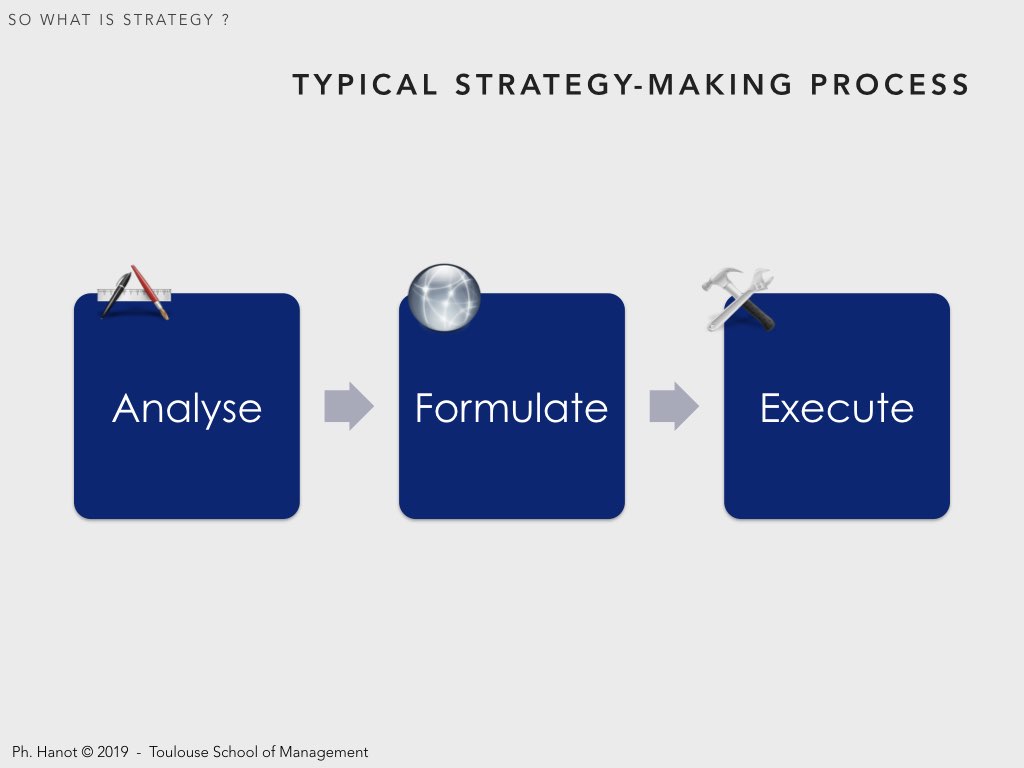

Most models & methods (at least when a deliberate strategy is elaborated) hinge upon a three-stage elaboration process although they may offer distinct perspectives on the goals, activities and approach.

Three step strategy making

Three-step strategy making.

Strategy formation is usually depicted as a three-step process : analysis, formulation and execution. :

Analysis – In a first step, both internal (self evaluation) and external environment must be appraised. The analysis should encompass both macro-environmental and micro-environmental (the industry, competitors, etc) considerations. It aims at gathering facts and figures but also at figuring out trends and possible evolutions.

Formulation – When their landscape is known and understood, firms produce a clear set of recommendations (or strategic plan), with sup- porting justifications. Recommendations may propose to revise and/or update the missions, goals or objectives of the organization. It is usually considered that a good recommendation should be effective in solving the problem(s) while ensuring a good level of ’fit’ between the resources and competences and the external environment. It should also be feasible within a reasonable timeframe, reasonable budget and without overly disruption for the organization. And above all, it should be (made) acceptable to the various stakeholders in the organizations.

Execution – Once approved, a strategy must be effectively and consistently implemented by the organization. Lack of sustainable and consistent commitment is one of the major pitfalls in strategy execution and probably the first reason for strategy implementation failures.

Strategy Elaboration is also a ‘Social Process’

In practice, the three steps are not as sequential as depicted by the usual ’standard process’. Furthermore, it is not uncommon to proceed by successive iterations (a bit of analysis, a bit of formulation, then back to analysis and formulation, etc).

Strategy-making is also a social process.

Iteration – Conducting a comprehensive analysis before stepping to the formulation stage would be very time consuming and probably inefficient. Usually firms run successive analysis-formulation loops. Candidate strategic moves are identified (formulated) further to a first analysis. Then subsequent analysis-formulation loops are handled, to refine the candidate projects and eliminate some. When projects are considered sufficiently robust and justified, a final recommendation is made to decision makers.

Buy-In – Strategic recommendations usually challenge the status quo and propose to walk out from the established comfort zone. Experience shows that when strategic recommendations are established in isolation from the rest of a firm, they are likely to be (at least at first) rejected by internal stakeholders. Strategists must therefore, leave their ivory tower and make sure that some stakeholders representing the various firm’s Functions (or departments) get involved and familiar with the analysis and formulation as soon as possible. However, internal stakeholders can be very complacent with the current situation and/or extremely reluctant when it comes to breakthrough changes. Strategists may choose to perform some analyses alone (or possibly with external support) to avoid distortions. These results can then be shared with other internal stakeholders to raise their awareness.

Explain – Once established, a strategic recommendation must be explained first to the decision makers, then to internal stakeholders (to get it executed) and also to external stakeholders (customers, suppliers, media, shareholders, rating agencies, etc). It is paramount to make it very simple, comprehensible and as crisp as possible. If you cannot articulate your strategy in a one-minute elevator ride, or put it in a single piece of paper (with no buzzword, no techno-geek stuff and no implicit statement) it is likely that strategy will never get executed.

Story telling – Story telling is inherent to strategic move. It is always a good sign when co-workers and/or external analysts start to ’recite’ the story. However, it would be a mistake to reduce strategy formulation to the production of catch phrases or tag lines. It is not straightforward to craft a simple, compelling story. It is usually the result of a comprehensive and deep strategic analysis.

Feedback – Last but not least, it is always useful to ensure explicit feed- back between execution (the strategy that get actually implemented) and formulation (the intended strategy). Discrepancies between the two can reflect changes (in the external and or internal environment), which would require adjusting the strategy formulation. It may also be the sign that the intended strategy not rightly implemented, which also require revisiting the strategy formulation to make sure it is better understood and execu- ted..

Strategy elaboration is also a social process, in so that the involvement and support of all stakeholders must be explicitly built as part of the elaboration of strategy..

« A successful strategy execution process is seldom a one-way trickle-down cascade of decisions.» ( [Vermeulen] )