Resource View of the Firm

The strategic management literature considers that broadly speaking there are two sources of superior profitability:

industry attractiveness which stems from market power, barriers to entry, etc and can be assimilated to what economists call monopoly rents,

scarce resource control (firm-specific assets such as patents, trademarks, brand reputation, distribution channel, key technologies, installed base, etc) that economists call Ricardo rents.

With the market-based view, also known as the outside-in or positioning approach, firms see themselves through the industry and market they serve. The key strategic questions are ’what is our business?’, or ’what are the customers’ needs that we fulfill?’. By contrast, the resource-based view of the firm adopts an inside-out approach and focuses on the firm’s internal capabilities: ‘what are our specific skills and capabilities?’, ‘what do we do better than the others?’.

The proponents of the resource-based view (or Resource-based theory) of the firm, outline that in a fast changing external environment, internal resources and capacities can provide a more secure foundation to long-term strategy.

For RBT, resources are “ the stock of available factors that are owned or controlled by the firm ” ([Amit93]) and strategy becomes the continuing search for rent or return in excess of a resource owner’s opportunity costs, where owning a competitive advantage can drive above normal rates of return.

Examples

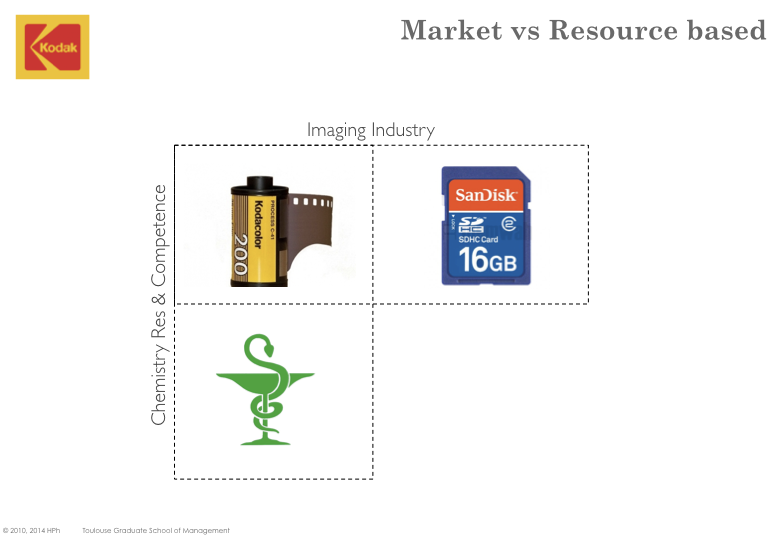

The Kodac Case

KODAC was the undisputed leader in chemical imaging photographic products. However, with the introduction of a superior product (digital photography) returns dropped quickly. In response, KODAC decided that coping with this new substitute would be its number one strategic priority

For years, Kodak has unsuccessfully invested billions to fight against emerging technologies and to transpose its leadership to digital imaging, considering it was still the same industry and it wanted to restore its leadership position. Grant raises the question : „might have KODAK been better-off sticking with its chemical know-how and developing its interest in specialty chemicals, for instance, pharmaceuticals or healthcare” ([Grant, 2006]).

Google seats in various industries

Google was established in 1998 as a web search engine company. In this ’industry’ Google faced Yahoo, Bing and other similar firms specialized in indexing and retrieving web pages. Soon, Google extended its activities and entered other industries (then facing new competitors) such as software applications (Maps, Chrome, Google Apis), operating systems (Android), Web content & social net- works (Google news, Google+, gmail), application and data hosting (Google cloud).

In the words of Larry Page & Sergey Bin the co-founders, Google’s mission is „to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. Google doesn’t see itself through either the markets they address (it may change over time) or their competitors. On the contrary, they define themselves by a set of capabilities.

The Resource-based Theory

The Resource-based model results from the contributions of several pivotal scholars such as ( [Amit93] [Barney91] [Barney97] [Peteraf93] [Teece97] [Wernerfelt84] ) and was initially formalized by Barney in his seminal article of 1991.

Development of the theory

The initial development of the Resource-Based Theory (RBT) of the firm ([Wernerfelt84, Wernerfelt95]) was aimed a re-stating Porter’s results from a different perspective (hence the initial name Resource-Based ’View’).

In 1984 Wernerfelt published an article where he suggests that Porter’s theory of competitive advantage could be restated from the assumptions that firms develop or acquire capabilities. In this perspective the resource-based view of the firm is a dual representation of the market-based view. While Porter had focussed on barriers and mobility constraints among industries, Wernerfelt’s intuition was that the competitive advantage a firm enjoys in the market had to be tied to some internal resources it controls, has acquired or developed. Indeed, the Resource-Based View considers that a competitive advantage derives from specific resources & competences controlled by the firm. RBV sees a firm as a set of resources and capacities that can get configured to over perform competition, hence leading to competitive advantage. Therefore the RBV does not point at the industry structure but at the unique cluster of resources and capabilities that each organization possesses and/or want to develop.

The same year Rumelt published a paper where he establishes a theory of firm performance, rooted in the resources that a firm controls and its capacity to generate economic rents. To a large extend he also considers the conditions under which a firm would be the adequate way to generate and capture economic rents as opposed to other form of organization (this is also the question addressed by Williamson through the Transaction Costs theory, although from a different angle). Teece (1980) merged the two theories and argued that the relations among business that are the most likely to be a source of economic profit (resource-based theory) are also the kinds of relations that are difficult to manage through non-hierarchical forms of governance (opportunism risk associated with transactions costs).

As highlighted by Grant ([Grant, 1991]) the development of the Resource-based theory as an alternative to the market view, may be an answer to fast changing customers needs: „In a world where customer preferences are volatile, the identity of customers is changing and the technologies for serving customer requirements are continually evolving, an external focused orientation does not provide a secure foundation for formulating long term strategy. The firm’s own resources and capabilities may be a much more stable basis on which to define its identity” ([Grant, 1991]).

In 1986, Barney showed that if firms would acquire strategic factors from a perfectly competitive market then this market would anticipate the performance that these factors would bring when used to implement product market strategies. In such an event, even imperfectly competitive product market would no longer be the source of economic rents.

Itanami (1987) introduced the concept of invisible assets (information-based resource, technology, customer trust, brand image, control of distribution, corporate culture and management skills). He considers that while physical assets are necessary, invisible assets are the source of outperformance because they are hard and time-consuming to accumulate.

Key Assumptions of the theory

Organization are not identical: they have different capabilities, in other words resources are heterogeneously distributed among firms (i.e. not all firms own all resources). Scott ( [Scott08] ) stresses that the relevance of a resource is highly contextual and depends in particular with the selected business model. A resource can be key to one firm and just not fit with another within the same industry.

Resources are imperfectly mobile (i.e. resources stick with their owner) and therefore differences between organizations are rather stable. This explains the existence of differences across firms in resource endowments and why this differences may persist over time [Barney 91].

A competitive advantage & superior performance of a firm is explained by the distinctiveness of its capabilities. Acquiring specific capabilities is usually a long and costly process. In addition, it may be difficult to establish a causal relationship between a level of performance and a set of capabilities. The Resource-based model hinges upon the assumptions that 1) a firm can hold a competitive advantage if it controls and exploits capabilities that are both valuable and rare, 2) a firm can sustain this advantage if capabilities are inimitable and non-substitutable and 3) this translates into long-term over-performance.

Resources, Capability & Competences

The resource-based theory encompasses several branches and school of thoughts, each with its own specific field of study and objective.

| Approach | Main authors | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Resource-based view | Barney, Wernerfelt | Identify and value VRIN resources to generate sustainable competitive advantage. |

| Core Competence | Hamel and Prahalad Amit and Schemaker |

Identify, focus and exploit core competences. Derive product/market presence from the core competence of the firm. |

| Dynamic capacities | Tiece Pisano and Schuen |

Identify t or acquired as to better match the evolution of market demand, products and technologies |

| Evolutionary Theory | Nelson and Winter | Adapt and refresh the internal routines and organization of firms. |

The resource-based approach helps explaining why a company possesses a competitive advantage (single business) and/or a corporate advantage (in the set of businesses it operates).

„While a competitive advantage may be achieved by luck, a sustainable advantage requires a resource and competence-sensitive strategy process” ([Barney, 1986]).

„A firm’s ability to earn a rate of profit in excess of its cost of capital depends upon two factors: the attractiveness of the industry in which it is located and its establishment of competitive advantage over rivals. Business strategy should be viewed less as a quest for monopoly rents (the returns to market power) and more as a quest for Ricardian rents (the return to the resources which confer competitive advantage over and above the real costs of the resources).” ([Grant, 1991])

Although the wording may vary among academics (and also among practitioners) the model hinges upon the concept of a specific bundle of resources that a firm has built up and accumulated over time (resources are stocks of assets and capabilities). Firms are therefore constrained by the resources they possess but also protected if it takes time for competition to copy their very resources.

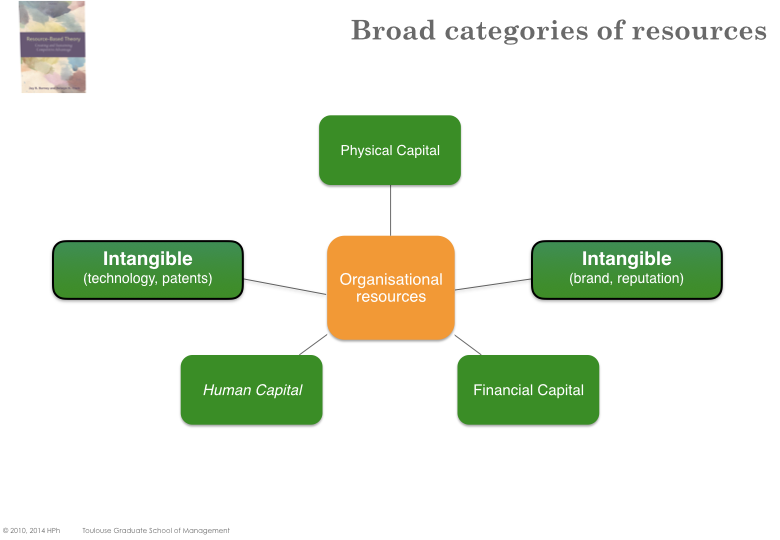

Categories of resources

There are fundamentally four categories of resources:

Physical capital geographical location, plants, machinery and physical technology,

Financial capital equity, debt, access to debt market, rating,

Human capital training, experience, insight, judgment,

Organizational resources firm culture, reporting structure, formal and informal planning, controlling, reputation

Resources may be thought of as inputs that an organization possesses or can call upon (e.g. from suppliers) to carry out its activities. Resources can be i) tangible (cash, geographical location, buildings, machinery and equipment, land, mineral reserve,), ii) intangible (technology, patents, copyright, brand name, reputation and notoriety, brands, customer, relationship, culture) or iii) human (skills, know-how, motivation, organizational capabilities, company culture).

A resource is something that the firm holds and can use to generate value. A resource can be viewed as a productive asset that the firm controls. The tangible, physical resources usually appear on the balance sheet of the firm. By contrast, accountants don’t measure other resources except in case of acquisition (where some resources can ’indirectly’ be recorded as ”Goodwill”).

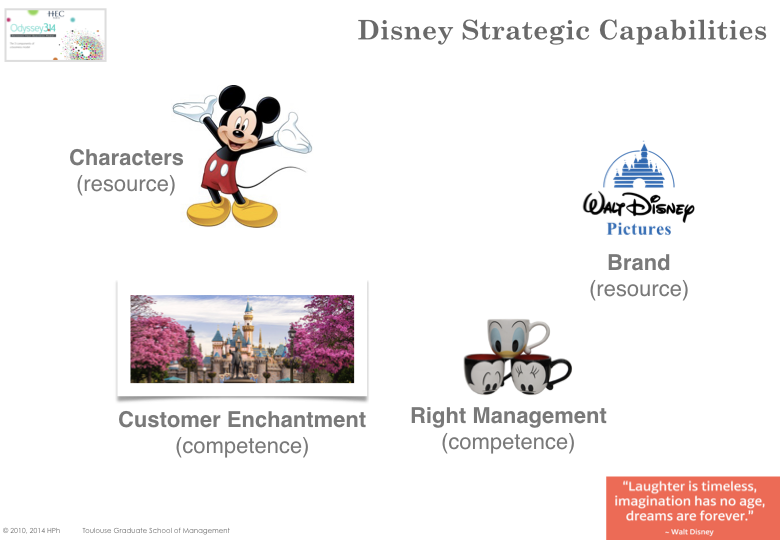

Competence or Capabilities

Essentially, RBT conceptualizes the firm as a bundle of resources. It is these resources, and the way that they are combined, that makes firms different from one another and in turn allows a firm to deliver products and services in the market. However resources in themselves do not confer any value to organizations. Resources have a potential use but alone are unproductive and do not confer any value in themselves to organizations. Value generation requires combining the adequate resources and the necessary skills. Competences are the most intangible and correspond to the activities, modus operandi and processes through which a firm can effectively use its resources. A competence is what a firm does well.

Organizational capability requires the expertise of various individuals to be integrated with capital equipment, technology and other resources (e.g. a brain surgeon if of little value if not complemented by an hospital, surgical instruments and equipment, a full team of skilled people, etc).

„There is a key distinction between resources and capabilities. Resources are inputs into the production process but on their own few resources are productive. Productive activity requires the cooperation and coordination of teams of resources. A capability is the capacity for a team of resources to perform some task or activity. While resources are the source of a firm’s capabilities, capabilities are the main source of its competitive advantage” ([Grant, 1991]).

Specific capabilities correspond to the (possibly unique) technologies mastered. Capabilities are activities that the firm does particularly well compared to competition. For instance, CANON offers a large spectrum of apparently uncorrelated products: camera, printers, fax-machines, copy-machines, video camera, etc. In all these products, a few fundamental capabilities are paramount: precision mechanics, micro-electronic and fine optics.

Likewise, 3M built its impressive product portfolio (in excess of 30.000 products) on the foundation of i) a few key technologies: adhesives, thin-film coatings and ii) the ability to market and launch new products. (adapted from [Grant, 2006])

Jon Kay ( [Kay95] ) distinguishes three fundamental types of distinctive capabilities:

Architecture comprises the system of contracts and relationships between the firm and its ecosystem (employees, customers, partners, suppliers, distributors, etc). Organizations depend far less on individual leaders than they do on their established structures, dominant styles and organizational routines (ways of working). Often, the relationships will be implicit and complex, with little formalization if any. In markets where the quality of products is derived from long-term experience, reputation is usually also a source of distinctive capability.

Reputation brand notoriety, customer’s experience, quality signals, word of mouth spreading, etc. A well managed reputation can be extended to new products

Innovation new technologies, new processes, introduction of new pro- ducts, but also finding applications for existing underused technologies (e.g. 3M derived post-it notes from low-quality adhesive).

Distinctive capabilities are necessary but not sufficient for success. Capabilities must also be sustainable – it needs to persist over time – and appropriable (i.e. to benefit primarily to the organization rather than its employees, its customers or its competitors). A sustained competitive advantage occurs when an organization is implementing a value-creating strategy that is not being implemented by current or potential competitors and when these competitors are unable to duplicate the benefits of the strategy. A competitive advantage may get eroded as the industry changes but won’t get competed away by competitors

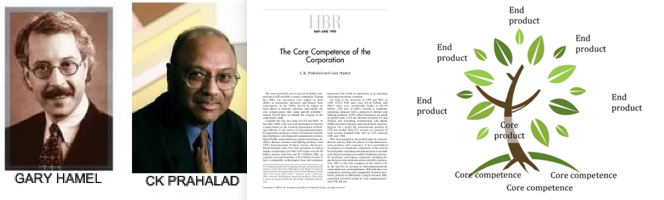

Core Competence

Prahalad and Hamel ( [Prahalad90] ) call core competence any competence that a firm masters particularly well, compared to its competitors.

In their view, a ”Core competence” i) should provide access to a wide variety of markets (e.g. Honda’s capabilities in engine design - cars, lawnmowers, powerboats), ii) should make a significant contribution to the perceived customer benefits of the end products (e.g. BMW, excellence in engineering) and last but not least, iii) it should be difficult for competitors to imitate.

In addition, for a core competence to have any lasting value to the organization the competitive advantage that derives from its use must be sustainable. In their seminal paper, Prahalad and Hamel emphasize that „in the short-run a company’s competitiveness derives from price/performance attributes. However competitors are all quickly converging on similar standards for product cost & quality. […] In the long-run competitiveness derives from an ability to build , at a lower cost and more speedily than competitors, the core competence that spawn unanticipated products”.

The real sources of advantage are to be found in management’s ability to consolidate corporate wide technologies and production skills into competencies that empower individual business to adapt quickly to changing opportunities.

Core competencies are the collective learning in organization, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies. Unlike physical assets that do deteriorate over time, competencies are enhanced as they are applied and shared (knowledge also fades away if it is not used). Competencies are the glue that binds existing business and are also the engine for new business development. Pattern of diversification and market entry can be guided by competencies and not just by market attractiveness.

Dynamic Capabilities

The ability of a firm to renew and recreate its strategic capabilities and meet the needs of changing environments, is in itself a key strategic resource. Indeed capabilities that are the basis of competitive success soon get copied by competitors and become standard practice of the industry. To continue to be effective overtime, capabilities can’t remain static but on the contrary need to adapt. By and large, three categories of dynamic capabilities can be identified: i) ability to sense new opportunities, ii)ability to seize an opportunity (i.e. to make a choice) and iii) ability to re-configure the firm’s capabilities.

More than the list of capabilities that a firm controls, what matter is the relative level with respect to competition in the capabilities that significantly contribute to the realization of the core business. When the firm is short of some capabilities, the management must create an imbalance (what Hamel & Prahalad call “stretch & leverage”), that forces the company to increase its capabilities to become more efficient and effective relative to competition.

The difference between the capabilities that must be controlled to become a significant player and the capabilities already controlled by the firm is a way to measure the level of matching (or strategic fit). However, the analysis must not be limited to systematically filling a grid, but on the contrary to highlight the few capabilities that are decisive to enter a business and generate sustainable profits.

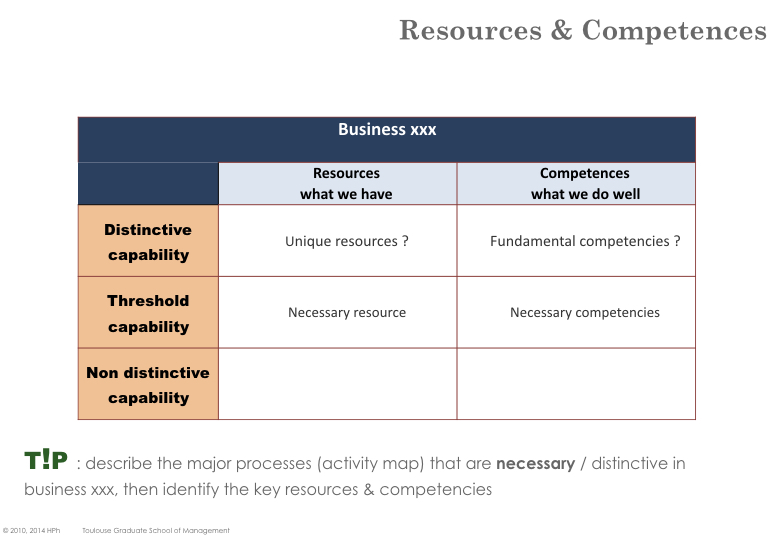

A Threshold Capability is the capability level needed to meet the necessary requirements to exist in a given market and/or establish a business.

A Distinctive Capability is the capability level that may be the basis of achieving competitive advantage and delivering superior performance.

When gaps are identified (and there are usually gaps), the firm can explore various options to fill them. First, the firm can try to develop ”in-house” additional capabilities (acquire the missing resources, learn new competence). The firm can also look for other companies that could be complementary and bring the missing capabilities through alliances, partnerships or merger

According to the RBT, the basis of competitive advantage may lie in aspects of the organization that are difficult to discern or be specific about. However capabilities are highly dynamic (competitors may manage to copy or imitate a set of capabilities) and therefore they must be carefully and proactively managed. Firms have fundamentally three options to manage strategic capabilities:

Internal capability management a firm may decide to reinforce its existing capabilities. This includes i) leveraging capabilities from one area of the business to others and ii) stretching capabilities i.e. build new services / products out of existing capabilities.

Growing capabilities through external developments such as M&A and/or Strategic alliance building.

Ceasing activities when the gap becomes too high or the advantage too narrow, a company may be better off exiting this specific area of business and refocussing on other domains.

Collins & Montgomey’s Framework

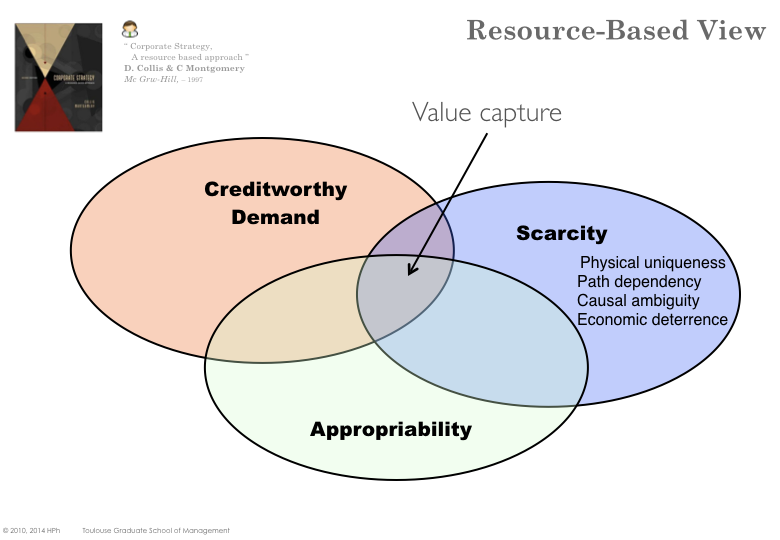

Collins & Montgomery ( [Collins95] ) [Collis1995]) consider that ”Value creation” lies at the confluence of demand, scarcity and appropriability. Value is created when a resource is demanded by creditworthy customers, when it can barely be replicated by competition and when the firm can easily capture the profit it generates. According to them „the challenge for manager is understand what distinguishes valuable from pedestrian resources and to use that knowledge to craft strategies that generate an enduring competitive advantage.” (ibidem)

Creditworthy demand

A resource is valuable to the extend that is meets customers’ demand and allow to serve customers better than competition. Although it sounds obvious, firms tend to forget that a valuable resource must help meeting customer demand and fulfilling a customer’s need at a price the customer is willing to pay.

An analysis of a firm’s resource should therefore not focus on an internal assessment only but also clarify how the firm’s stock of resources translate into fulfilling customers’ expectation better than competition. In addition, as both customer demand and alternate value proposition may evolve, firms must reassess periodically the value of their resources and try to anticipate losses of value.

„A resource value derives from its application in product market. It traces back from the ultimate satisfaction of customers” (Peteraf & Bergen)

„A resource is valuable if it can generate in someway a rent stream from a product market that can be captured by the firm. A valuable resource must contribute or be involved in the creation of a product or market that has value to customers” (Bowman).

Scarcity

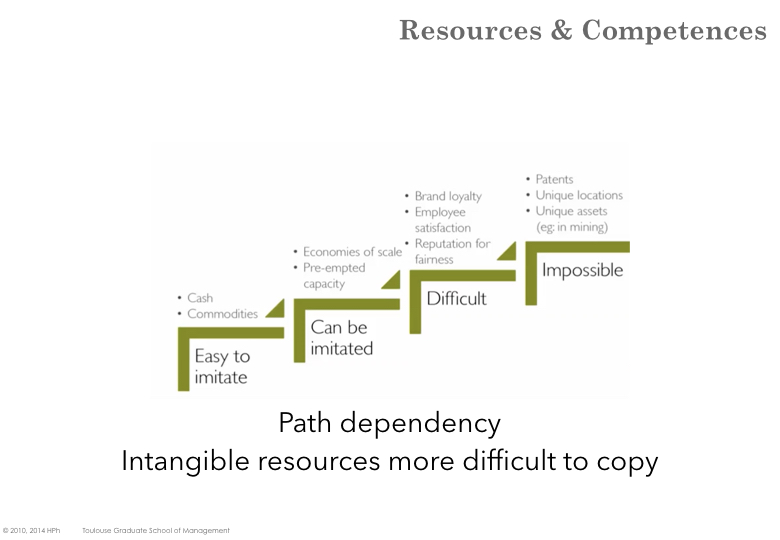

However, not all the resources that contribute to meeting customer’ demand can provide a competitive advantage. The condition is necessary but not sufficient. If the resource that the firm possesses is not in short supply of if it can be easily copied or replicated by competition, it is unlikely that it can yield any competitive advantage. Resource scarcity is therefore the second requirement for a resource to contribute to competitive advantage. According to Collins & Montgomery there are four characteristics that make resources rare and difficult to imitate.

Physical uniqueness – geographical location, patent, mineral extraction rights, etc. Although firms believe they are well protected against competition when the hold physically unique resources, it however often turns out that such resources are easier to imitate or substitute than expected.

Path dependency – most resources needs to be gradually accumulated over time (brand name recognition, R&D knowledge, organizational capabilities, etc). Imitators usually need to re-create the path that predecessors took, which protect the first-entrant by delaying imitation. However, when the actual valuable resource is easy to identify, imitator may catch up quickly with the pioneering company.

Causal ambiguity – external observers can usually infer some correlations between competitive advantage and resources but may fail to disentangle what the truly valuable resource is.

Economic deterrence – occurs when i) resources are scale sensitive (e.g. capex) ii) the market leader has the capabilities to replicate its resources (e.g. factory) but iii) choses not to do so as market demand is limited. If in addition the resources are specific to a given market (sunk costs), they represent a ’credible commitment’ that the leader will remain in the market and react to any newcomer attempting to enter the market

Value Capture

Meeting customers’ demand and resource inimitability are good ingredient to generate value. However a firm will usually also seek to appropriate and capture value and avoid that somebody else can claim most of the value. When property rights to the resources are clearly established, profits will flow to the owner of the resources. For this reason, firms are more likely to appropriate profits from the resources they develop themselves than from those they purchase in the market. However there is always a risk that the firm has to pay out its profit to some of its stakeholders (e.g. high salaries to general managers, salesmen, …).

Value Frameworks

The VRIN Framework

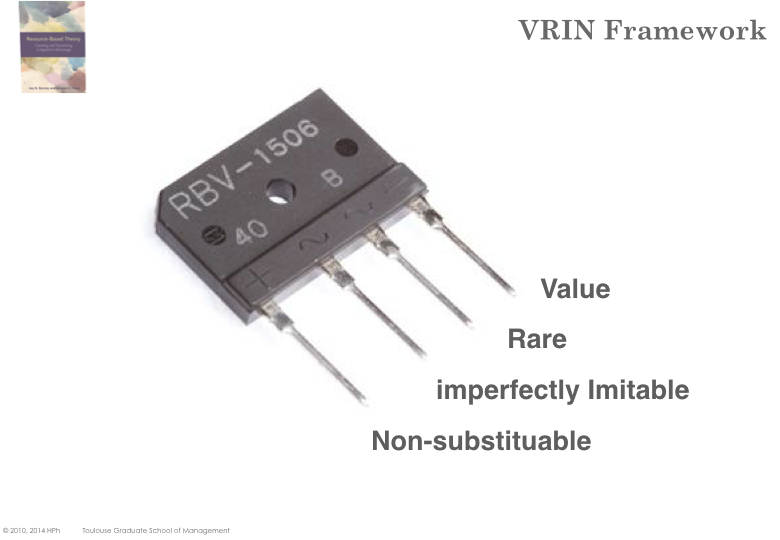

Barney ([Barney, 1991]) put forward the popular VRIN checklist to identify whether or not a capability can be strategically important. It underlines on what bases organizational capabilities might become the foundation for sustainable competitive advantage and superior economic performance.

Valuable

Obviously a resource (or capability) would be of little use if it doesn’t deliver acceptable return to the firm. A firm should not keep a resource that is not (and cannot be made) valuable. According to the RBV literature, valuable resources are resources that allow a firm either to claim for a premium pricing or to lower its cost compared to its competitors. Barney considers that a valuable resource must enable a firm to do things and behave in a way that lead to higher sales, lower costs, higher margins or in other ways add value to the firm. In other words, resources are valuable when they enable a firm to either improve its efficiency or effectiveness. A valuable resource must allow either exploiting opportunities and/or neutralizing threats. Note : when assessing whether or not a resource is valuable, the key question must be ’valuable for what’ (indeed, a resource can barely be valuable in absolute terms, even the concept of ’resource’ is not absolute).

Rare

A firm enjoys a competitive advantage when it creates more economic value than its average competitor. If a valuable resource is highly available among competitors then it is unlikely that it can be the source of any significant advantage. A bundle of resources can generate a competitive advantage as long as the number of firms that can use these re- sources is low compared to the total number of firms in that particular industry. Capabilities that are owned by a large number of firms cannot confer competitive advantage, indeed if competitors have similar capabilities they can quickly respond to any strategic initiative. A Capability that is not rare can still be necessary ; it won’t be considered strategically important though.

Inimitable

Valuable and rare resources can only be a source of sustainable competitive advantage if the average player cannot easily replicate or obtain these resources: the cost of getting a resources should exceed the likely economic profit it would yield. Otherwise, any competitive advantage will be short-lived. Barney outlines three reasons why resources would be imperfectly imitable (or costly to imitate):

ability to obtain the resource is dependent on unique historical conditions (including first-mover advantage or ripple effect from resources acquired in the past)

link between the resource and the advantage is causally ambiguous (i.e. it is not easy to understand which are the resources that yield the advantage and this is often true of the firm that enjoys the advantage. Indeed very often managers consider some resources as implicit and cannot easily outline the firm’s recipe for outperformance. For instance because some intangible assets – e.g. teamwork – can be hidden and/or because a complex network of interrelated intangible and organizational resources is at play)

resource (capability) is socially complex - which includes interpersonal relationships ; a firm’s culture, a firm’s reputation among its peers, its suppliers and customers.

Non-substitutable

There must be no strategically equivalent valuable resources that are themselves neither rare nor inimitable. It is generally argued that to achieve strategic advantage from a capability it needs to be developed internally and should not be freely traded in the market. In- deed, if a valuable, rare and imperfectly imitable resource can be easily substituted by a set of resources that would yield similar effects while being easy to duplicate and/or easy to acquire at low cost then it is unlikely that any competitive advantage can be long lasting.

The VRIO Framework

Before being re-dubbed ’VRIN’, Barney’s framework was known as ’VRIO’ where ’O’ stands for Organized.

The thought behind stressing that a firm had to be aligned with its own strategy was that possession or control of VRIN resources is necessary but not sufficient to gain an advantage. Indeed the firm must be ready to leverage its re- sources and capture value. This encompasses capacities such as incentive and monitoring systems, formal and informal reporting , interface and collaboration among customer facing and support Functions. In other words, a firm that possesses a valuable and rare resource will not gain a competitive advantage unless it can actually put that resource to effective use.

„ For instance, for many years Novell had a significant competitive advantage in computer networking based on its core NetWare product. In high-technology industries, remaining at the top requires continuous innovation. Novell’s de- cline during the mid- to late 1990s led many to speculate that Novell was unable to innovate in the face of changing markets and technology. However, shortly after new CEO Eric Schmidt arrived from Sun Microsystems to attempt to turnaround the firm, he arrived at a different conclusion. Schmidt commented : ”I walk down Novell hallways and marvel at the incredible potential of innovation here. But, Novell has had a difficult time in the past turning innovation into products in the marketplace.” He later commented to a few key executives that it appeared the company was suffering from ’organizational constipation’. Novell appeared to still have innovative resources and capabilities, but they lacked the organizational capability such as product development and marketing, to get those new products to market in a timely manner.” (Stephen Laughnet - Principles of Management)

This example stresses how much it is important to ’start with the end in mind’ and thoroughly identifies all the resources that are needed. A fantastic research lab with track records in unveiling breakthrough technology (e.g. the Palo Alto Research Centre invented the laser printer, the graphical user interface, the mouse device, the ethernet and tons of other technologies) is a rare resource, but if the objective is to deliver innovative product to the market (i.e. capturing value from the innovation) then producing innovation is just half-way to the target. Once all the capabilities (or resources) are identified, the firm must look for ways to derive a sustainable competitive advantage, that is ensure that at list some of the resources are rare, imperfectly imitable and non-substituable. It is paramount to understand that an uncorrelated bundle of VRIN resource is usually yielding no value at all.