Vertical Boundaries

« The production of any good or service usually requires many activities. The process that begins with the acquisition of raw materials and ends with the distribution & sale of finished goods and service is known as the vertical chain » [Besanko]

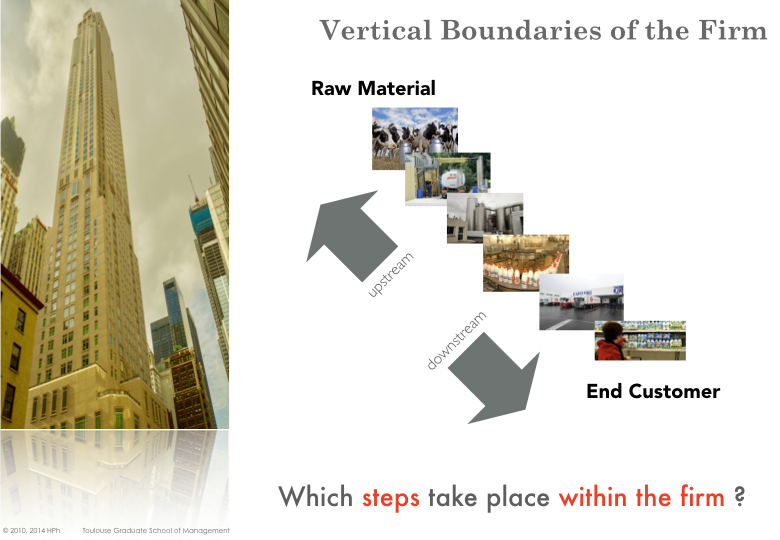

Vertical Boundaries of the firms

First, a firm needs to decide where it wants to operate along the Value System (or vertical chain). Any production process can be described as a sequence of stages (including inbound and outbound logistics, distribution and retailing) that flows from the raw inputs to the end customer. The vertical boundaries of a firm delineate the activities that the firm performs on its own, as opposed to purchases from the market.

Note: Each stage can represent an industry in its own right, which is subject to specific competitive forces).

Within the production process, upstream activities are close to raw material and downstream activities to the end consumption.

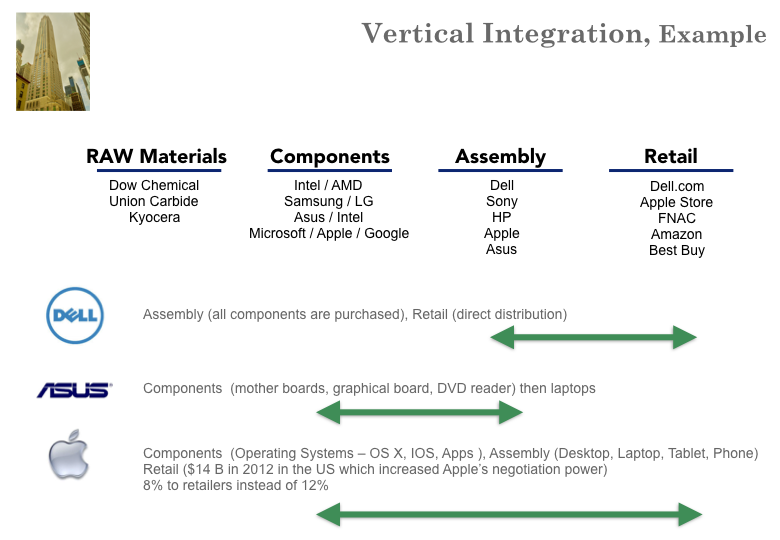

A firm that participates in more than one successive stage of the process is vertically integrated. Integration can be achieved through external growth (e.g. acquisition) or organic growth (green field development).

A backward integrated firm produces its own inputs whereas a forward integrated firm becomes its own ’customer’ (but there still should be some ’end customer’ at the end of the value chain). Integration can be hybrid in so that a firm may for instance decide to build some of its inputs while still relying on its suppliers for other inputs.

As an alternative to integration, a firm may decide to establish strategic alliances and/or tight contractual relationships with some upstream or downstream firms (e.g. franchise network). Such schemes are sometimes called quasi-integration. When a firm decide to outsource some activities (i.e. purchase from the market) this is called vertical dis-integration.

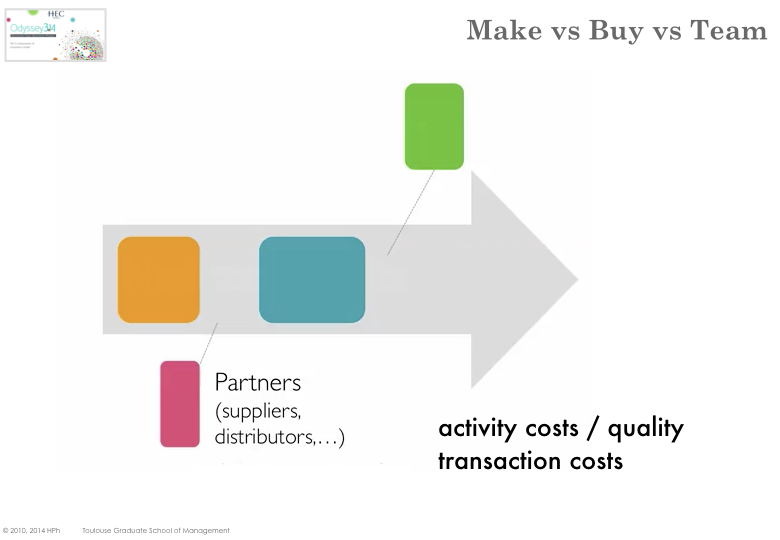

Make vs. Buy

The decision to rely on the market (buy from suppliers) or to produce internally (make) is often called a make vs buy decision. A highly integrated firm performs most activities in-house. For instance, Benetton dyes fabrics, designs and assembles clothing, and operates retail stores [Besanko]. Other firms focus only on the design of their products while having already outsourced all their production.

By and large, a firm will decide to make (i.e. to produce internally) if it has the capability, the capacity and if it can produce at a cost equal or less than what the market can offer. Otherwise the firm would decide to buy (i.e. to procure from a supplier).

It is noteworthy that Make vs Buy is not about deciding which production steps can be eliminated. Instead it is about deciding which steps should be performed in-house by the firm.

The external value chain describes how the business model of the company fits into a broader, sectoral logic. It underlines how the various players (suppliers, complementors) are contributing to value creation for customers. It may as well highlight which are the potential ways of improving the business model.

Classically several aspects must be taken into account before deciding to outsource activities:

Does it solve a problem? although an obvious question, companies sometimes fail to identify the problems (e.g. capacity, cost, competence) that they are seeking to solve, before looking for an external provider.

What degree of integration? with the other activities of the firm and how much is it contributing to the competitive advantage. Is the firm outsourcing activities or its complete business (which can be extremely risky).

Will it improve performance? i.e.reduce costs, improve quality, shorten lead-time, increase higher reactivity, etc.

Will it transform fixed costs into variable costs? reduce financial risks & capital expenditure, increase flexibility

Choosing the market usually brings several benefits such as

market firms can produce at a lower cost: i) as they aggregate the needs of many customers and serve a larger demand, they can achieve economies of scale (hence lower cost) that in-house production cannot, ii) being more specialized they can enjoy the experience effect earlier

specialized market firms can be more innovative or simply control a set of skills & competence that are not available internally

in a competitive market, firms seek to increase their efficiency and eliminate bureaucracy

However it may as well come with some drawbacks:

Coordination costs (production flows from different sources) and risk of production flow disruption

Transaction costs (see below)

Leaking of private information (Intellectual property, forecast, etc…)

Bureaucracy Effects

Although the term bureaucracy only appeared in the middle of the 18th century, it is associated with organized administrative systems that many forms of government have developed since 3500BC.

For strategists (and economists) however bureaucracy relates to control activities within a firm. It is often considered waste as i) it doesn’t directly contribute to the production process and ii) it is associated with conflict of interest, agency problems and influence costs.

We say that Managers and/or workers are shirking when they are not acting in the best interest of their firm.

Agency costs are the costs associated with i) shirking, ii) administrative audit and control and iii) deterrence measures to prevent shirking.A common way to limit shirking is to reward managers for the profit that their efforts contribute to the firm (bonus, stock options, etc…). However it is not always straightforward to evaluate such profit, even less for activities that are insulated from competition because they have captive internal customers.

Influence costs as Paul Milgrom and John Roberts ( [Milgrom90] ) call them, are another class of costs that often arise. The various departments or teams in a firm compete for funding, indeed there are often more ideas and requests than available budget. Managers will often seek to command more of their company’s resources to advance their career (and receive more personal reward), possibly at the expense of the company profit. To do so, manager may engage in a set of influence activities, including exaggerating the merits of their projects, badmouthing proposals from others, withholding information or key personnel. As a result of this asymmetry of information, resources (people, capital) are inefficiently allocated.

Transaction Costs

As stressed by Besanko, «Contracts list the set of tasks that each contracting party expects the other to perform and specify remedies in the event that one party doesn’t fulfill its obligations». If a firm could be certain that its partner would never shirk, there would be no reason for a contract.

A complete contract stipulates each party’s rights and duties for each and every contingency that could happen during execution. It is very challenging to specify a complete contract as all potential contingencies must be identified and the associated course of actions for the two parties precisely defined. In addition the required level of performance must be defined as well as means of measuring the actual performance during execution. Last but not least, the contract must be enforceable (for instance by a tribunal).

Most real-life contracts are incomplete (they don’t fully eliminate opportunities for shirking) mainly because i) it is non-realistic to identify all contingencies (even less for long-term contract), ii) it is very challenging to fully specify courses of actions and iii) very often the parties don’t have equal access to all information.

The concept of transactions cost was coined by Nobel prize winner R. Coase and initially disseminated by O. Williamson another Nobel Prize winner ( [Coase37] [Williamson81] ) . Coase stressed that if relying on the market was always more efficient than making within a firm, there would be no firm. He concluded that there must be some additional specific costs that are incurred when a firm buy from the market.

Williamson detailed what is encompassed into transaction costs: the time and expense of i) identifying suppliers, ii) seeking information, iii) negotiating, iv) writing and enforcing a contract as well as the costs incurred when suppliers exploit incomplete contracts to act opportunistically. Incomplete contracting always entails some transaction costs, the largest part of which being the adverse consequence of opportunistic behavior and the costs of trying to prevent them.

A factor is said to be Relation-specific when it supports a particular contract and cannot be redeployed (or at a significant cost). For instance a manufacturing die (used to cut and shape material using a press) is both expensive and specific of the part being built. If a firm use an external design office and impose non-standard formats (e.g. software, methodology, unwritten routines) the corresponding skills and competence are relation-specific. Physical locations (e.g. factory or warehouse nearby the customer) are also relation-specific factors. Williamson stresses that once the parties have made a relation-specific investment a fundamental transformation unfolds and the relationship evolves from “many options” bargaining situation to “limited or single option”.

The relation-specific investment is the portion of the investment that cannot be recovered in case the contract doesn’t materialize. The quasi-rent is the extra profit derived from the materialization of the contract compared to the next-best alternative once the investment is made. When an asset is specific, the quasi-rent is strictly positive (i.e. the next-best alternative is not as good as the contract materialization). At the extreme, the investment is so specific that the quasi-rent is the full profit of the contract.

Holdup problem if the quasi-rent is substantial (i.e. the supplier has a lot to lose), the customer may be tempted to exploit in one way or another breaches in the contract and renegotiate at a lower price once the investment is made.

Power plants are highly specialized assets. To avoid the hold-up problem (in developing countries), power plants are built on floating barges, thereby the geographic specificity can be partially eliminated and if a government defaults or seeks to leverage opportunistic behaviors, the power plant can be relocalized elsewhere at low cost. [Besanko]

Frequent Make vs Buy Fallacies

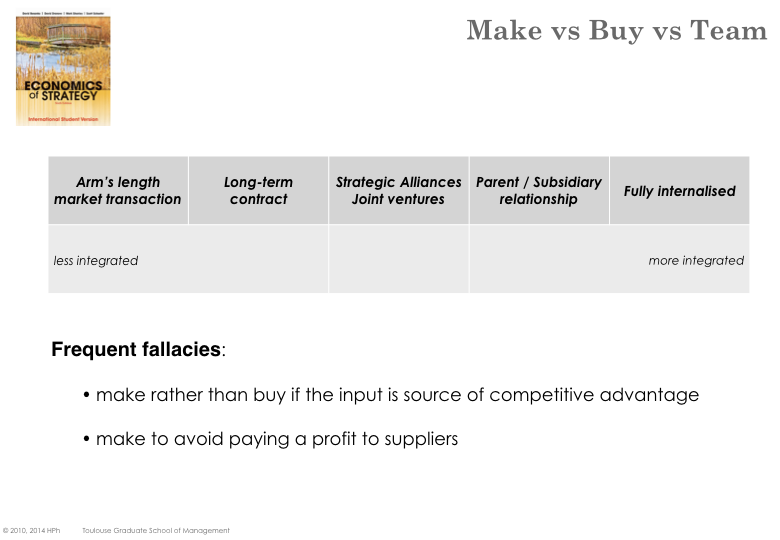

Make vs Buy is not black or White and there is a continuum between on the spot market access and full integration. Furthermore a firm may decide to insource some activities. This can be achieved organically or by acquiring one of the existing suppliers (or a firm that competes with the existing suppliers).

Firms should make rather than buy an input if that input is a source of competitive advantage. An input that can be (easily) acquired by any player from the market cannot be a source of competitive advantage.

Firms should make rather than buy to avoid paying a profit to a third party in other words, firm should backward integrate to capture the profit of its supplier. A Make or Buy decision must be looked at from the perspective of the firm and therefore the cost of making must be compared to the cost of purchasing (how much of that cost is captured as profit by the supplier is irrelevant).

Why seeking to vertically integrate ?

Vertical integration can be driven by several reasons:

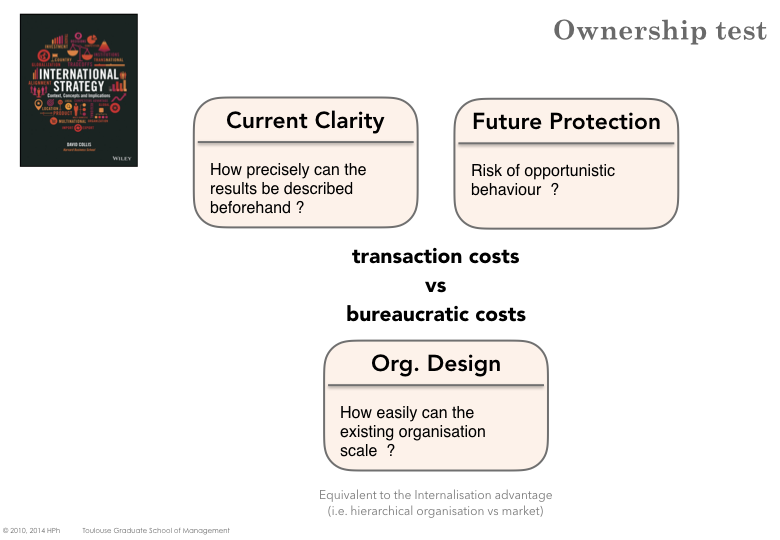

Transaction Costs a firm incurs costs besides the price when trading with other (e.g. searching and assessing potential suppliers, running selections, writing and enforcing contracts). A firm that vertically integrate avoids such costs (however it incurs new management and control costs).

Avoid opportunistic behavior it can be very difficult and costly to anticipate all potential situations in a contract. Therefore there is a risk that one of the parties may want to take advantage of the other if the circumstances permit. Usually the solution consists in signing long-term agreements, where most of the attributes of the relationship are clearly specified. However when the risk of opportunistic behavior is too high (for instance when a firm only deal with one other firm), integration is preferable to any commercial relationships.

Asymmetry of information when one firm owns private knowledge that can’t be taken into account when the contract is established, that firm is likely to seek taking advantage of the less knowledgeable firm. If the buyer anticipates the asymmetry, it will increase monitoring and will therefore incur additional costs.

Control quality and ensure steady supply when a supplier deliver components that are crucial, are difficult to store or represent high unit price, the buyer will try to control production. Alternatively, the buyer may decide to integrate its key suppliers and take full responsibility for the supply.

Avoiding regulation /Anti-trust firms may also vertically integrate to avoid government price controls, taxes, and regulations. A vertically integrated firm avoids price controls by selling to itself (internal transaction). Firms also integrate to lower their taxes. Tax rates vary by country, state, and type of product. A vertically integrated firm can shift profits from one of its operations to another simply by changing the transfer price at which it sells its internally produced materials from one division to another.

Eliminating Market Power a firm that faces direct suppliers or retailers that are too strong may try to either foster competition (even sometimes create competitors) or eliminate that market power by vertically integrating.

Property Rights of the Firm

Integration allows the firm to control resources, costs and profit when contract are incomplete and partners would disagree. When contracts are complete it doesn’t matter who own the assets.

According to Oliver Hart, Sanford Grossman and John Moore: « Integration determines the ownership and control of assets, and it is through ownership and control that firms are able to exploit contractual incompleteness. »

If a firm rely on a partner’s asset, it will have to persuade the partner to cooperate (or to execute the contract). By contrast, if the firm owns the asset it can decide (*residual rights of control *) how to use that asset as new opportunities unfold.