Concept of Business Model

What is a Business Model

First Definition

There are many definitions of the concept of Business Model. In a nutshell, a BM is a simplified representation of a business that stresses both the intent and inner logic ( [Osterwalder10] ) .

A Business Model is „the set of mechanisms by which a company can create value through the value proposition made to its customers, its value architecture and capture that value to turn it into profits” [Lehmann-Ortega].

Is the Concept useful to Strategy ?

Initially, Porter ( [Porter01] ) and with him many scholars strongly criticized the concept of Business Model arguing that it was ill-defined and not bringing any novelty to the field of strategic management. Business Model was one of these buzzwords that became prevalent with the Internet boom in the late 90’s. As stated by Joan Magretta ( [Magretta02] ) :

„a company didn’t need a strategy or a special competence or even any customers – all it needed was a web-based business model that promised wild profit in some distance”.

However the concept has gained momentum and although it does not replace any strategic management framework, it offers an effective way to describe what a company does, how it does it and why it can yield any profit (or not).

Communication and Self-Reflexion tool

The Business Model concept has become common place in many industries and is proving valuable as both a communication and self-reflexion tool.

The stakes are as much in the coherence, consistency of the strategic vision and enterprise architecture as in the ability to mobilize and convince the various stakeholders and materialize the vision.

Rethinking and improving a company’s strategy often starts with establishing a genuine model of its current businesses. This becomes even more crucial in a context where „economic instability became the rule and therefore requires the company to demonstrate constant agility in order to adapt and even create innovative solutions to ensure its development” ( [Vilain11] ) . The concept of Business Model has spread to strategic practices as a means of in depth checking of a strategic design.

As stressed by Grandval and Ronteau, the BM concept can be leveraged by strategists, to regain the freedom to formulate a strategic intention and guide the strategic action (in the original and military sense of the word strategy ). It can as well assist the management team in identifying and organizing the company efficiently and effectively through continuous business innovation.

Furthermore, a Business Model can be viewed as a didactic description of the strategic vision and its implementation. It help managers and entrepreneurs build narrative or stories in a coherent manner and allows for effective communication with the company’s stakeholders (customers, employees, partners, suppliers, investors). It is a valuable tool to get the different stakeholders involved and supportive

As underpinned by Joan Magretta (ibidem), Business Models are stories that answer Perter Drucker’s old age questions :

- Who is the customer ? Who is being satisfied ?

- What do customers value ? What are the needs, what is being satisfied ?

- How are customers being satisfied ? What are the distinctive capabilities ?

- How do we capture part of the created value (i.e. make profit ) ? What is the underlying economic logic ?

BM Conceptualization

Several different business conceptualizations have been proposed. Despite differences they all aim at building formal descriptions of business architectures from a set of building blocks.

Two well established models will be used instead: Odyssey 3.14 ( [Lehmann-Ortega15] ) and the Business Model Canvas ( [Osterwalder10] ) .

The Odyssey Model

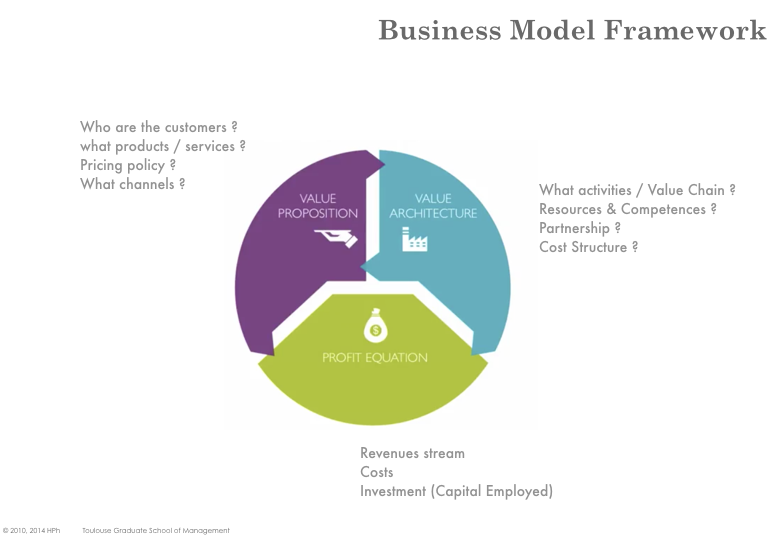

Odyssey, the simplest of the two models, emphasizes the three major aspects of any venture : WHAT is offered, HOW is it produced and can it be Profitable?

The model was designed by two professors at HEC and many students are likely to get exposed to it. The model is documented in a book and MOOCs are available as well. The model hinges upon three major components or pillars as the authors call them:

Value Proposition - the front-office aspects of any business: i) Who are the (possibly segmented) customers? ii) What products and services are offered? and iii) What pricing policy is associated to the various products and customers?

Value Architecture - how to deliver the value proposition: i) What are the required activities ? ii) What resources & competences are needed and are controlled by the firm ? iii) What is performed within the firm as opposed to outsourced to somebody else ?

Profit Equation - the quantitative summary of the whole: i) What are the revenues streams ? ii) What are the associated costs ? iii) What investments are required ?

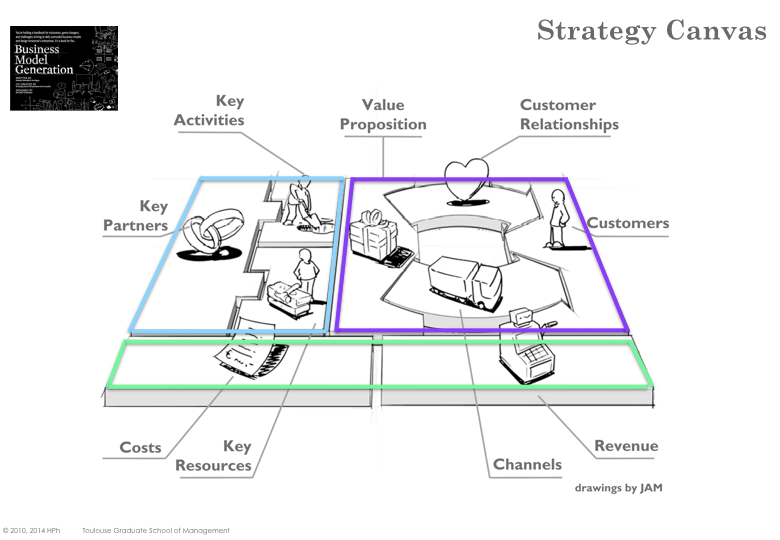

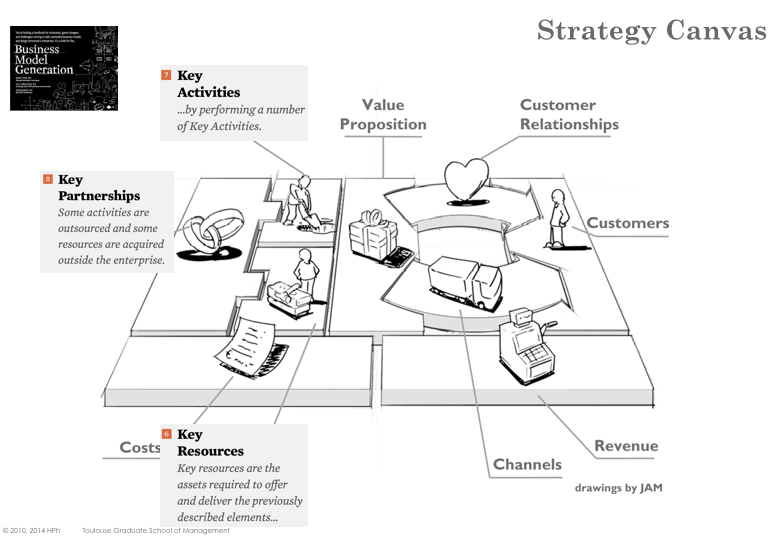

The Business Model Canvas

The business Model Canvas follows the same logic, but offers further refinements, by being more specific about the Value Proposition (including customer experience and interaction) and the Value architecture (including resources & competences and partnering).

Being very visual, the model (initially derived from A. Osterwalder’s academic work) is perfectly suited for group work for developing and documenting business models.

Compared to the Odyssey model, the BM Canvas is more detailed (i.e. top level components are further broken down into smaller constituents). However the very same rationale applies here as well.

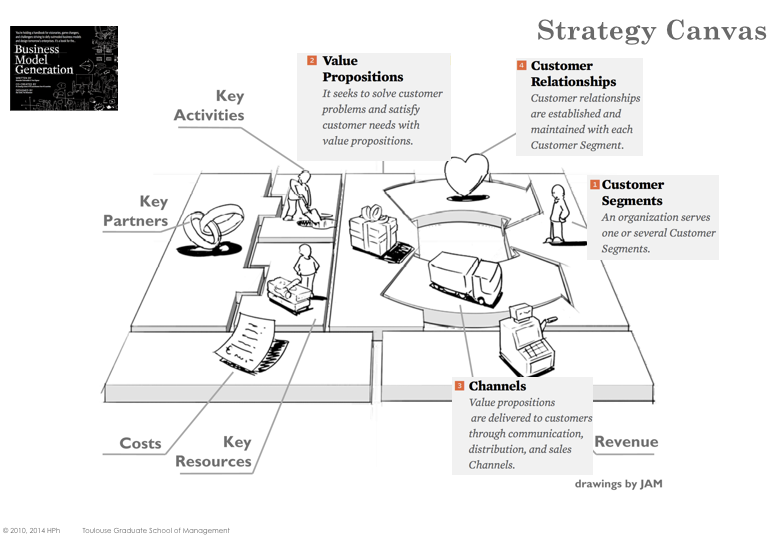

Customers - two aspects are key with delineating targeted customers:

i) Customer Segments a company must identify which customers it tries to serve. Customers can be segmented into various subsets, according to their specific needs and attributes. Typical market attributes encompass the size (e.g. mass market vs niche market) and whether it corresponds to personal or professional consumption.

ii) some companies will serve mutually dependent customer segments. A credit card company will provide services to both credit card holders while simultaneously assisting merchants who accept those credit cards. The ability to recognize a multi-sided platform is pivotal to many business models Indeed, one type of customers only (e.g. advertisers) can generate revenues, while the most obvious value proposition is targeted at another category of customers.Value Proposition - The collection of products and services a company offers to meet the needs of its customers. The value proposition can encompass various elements such as newness, performance, ’one stop shop- ping’, customization, ’getting the job done’, design, notoriety/brand/status, price, cost reduction, risk reduction, accessibility, and convenience/usability.

Channels - how a company reaches and engages its customer segments to deliver a Value Proposition. Channels are customer touch points that play a crucial role in the customer experience: raising awareness of the Value Proposition, evaluating the proposition relatively to alternatives, purchasing & ordering, receiving (delivery, shipment, …) the product or service and last but not least obtaining post-purchase support. A company can deliver its value proposition to its targeted customers through different channels: either through its own channels (store front, web site), partner channels (major distributors), or a combination of both. Effective channels will distribute a company’s value proposition in ways that are fast, efficient and cost effective.

Customer Relationship - this building block corresponds to the ways a firm wants to establish contact with a customer (mechanisms, timing, frequency, etc) for the purpose of customer acquisition, customer retention, up-selling and sales boost, etc. Customer loyalty is paramount to ensure the survival and success of any business. Companies must identify the type of relationship they want to create with their customer segments, which may include:

i) personal assistance during sales and/or after sales,

ii) dedicated personal assistance a sales representative is assigned to handle all the needs and questions of a special set of customers,

iii) self service the company provides the tools needed for the customers to serve themselves easily and effectively (typical of web-based business),

iv) automated service similar to self-service but more personalized as it has the ability to identify individual customers and his/her preferences. An example of this would be Amazon.com making book suggestions based on the characteristics of previous purchases,

v) communities allows for a direct interaction among different clients,

vi) co-creation the customer’s direct input is included in to the final company’s products/services (wikipedia is an example of co-created product).

Key Activities - underlines the most important activities (whether performed by the company or not) that are required to deliver the company’s value proposition.

Key Resources - (human, financial, physical and/or intellectual) necessary to carry out activities. Those activities for which the firm owns appropriate resources are usually performed in-house (‘make’ part). By contrast, the firm can choose to transfer some activities to external partners (‘buy’ part).

Partner Network - most companies rely on buyer-supplier relationships so they can focus on their core activity. Partnership, here also covers complementary business alliances (e.g. joint ventures, strategic alliances) between competitors or non-competitors. In case of ’multisided markets’, some Customers can easily get confused with Partners. For an external stakeholder to be a partner, the firm must transform the inputs it receives. For instance, content providers (movies, music albums, books) are more customers to i-tunes rather than suppliers/partners.

Profit - results from the difference between revenues and costs. The Business Model Canvas articulates the two sides of the equation and offer the opportunity to visually see how to increase revenues and/or reduce costs.

i) Cost Structure Characteristics it is essential to clearly identify Fixed Costs (including sunk costs) from variable costs.

ii) Revenue Streams the company must identify all the sources of its incomes and understand how each customer segment contributes to revenue generation.Even customers who are not responsible for any direct payment can contribute to generate revenues from other customer groups (e.g. network effect aka customer side economies of scale).

Relationships & channels

Osterwalder ( [Osterwalder10] ) stresses that there are different categories of customer groups, each leading to specific Customer Relationships and Distribution Channels:

Mass market - Business that focus on mass markets don’t seek to distinguish between customers. The Value Proposition as well as Distribution Channels and Customer Relationships target a large group of customers with very similar needs and expectations. There is very little customization if any.

Niche market - Along side large groups of customers, there might exist smaller groups with very distinct needs. Tailoring the Value Proposition, Distribution Channels and Relationships to one of this smaller groups can allow very successful business models.

Segmented market - Some firms would rather deal with more than one customer group (either mass market or niche market). Serving several customer segments often imply establishing several distinct value propositions but also dedicated distribution channels and distinguished customer relationships.

Diversified market - Firm can also decide to address unrelated customer groups (serve very different needs). When Amazon.com launched AWS they star- ted a different business and faced diversified (possibly segmented) customer groups. Offering diversified Value Propositions usually requires implementing different Value Architectures.

Multi-sided market - Firms can serve several interdependent customer groups. Unlike segmented or diversified business models, a multi-sided business model relies on the two (or more) sides and requires the adhesion of the two sides to be successful.

Customer Value Creation

A mix of several attributes both quantitative (price, speed of service) or qualitative (novelty, design) contribute to customer value creation, including :

Newness - A Value Proposition can satisfy an entirely new set of needs, often that customers didn’t perceive previously. Such VP can rely on new technologies (e.g. smartphone), new social habits (e.g. shared economy) or personal aspiration (e.g. ethical funds).

Performance - The offering is comparable in essence to the pre-existing reference point but deliver more performance (e.g. computer disk space, processor power, display resolution). In a very mature market, performance only is unlikely to yield any significant market growth.

Customization - Sometimes called customer co-creation, allows a large range of customization (e.g. color, shape, etc…) while still benefiting from standardization and economies of scale.

Getting the job done - Start from recognizing customer hassle and help reduce the pain.

Design - a product may stand out because of superior design and for aesthetic reasons.

Brand / Status - the perceived value is not necessarily purely functional (derived from using the product). Sometimes owning / wearing the pro- duct can be a social signal that conceals value in itself

Risk reduction - a value proposition may encompass elements to reduce the risks incurred by a customer (e.g. guarantee, fixed-fees, service-level agreement)

Accessibility - innovations and/or new technologies can make product/service available to new customers. For the business model innovator this is a way to address previously untapped markets.

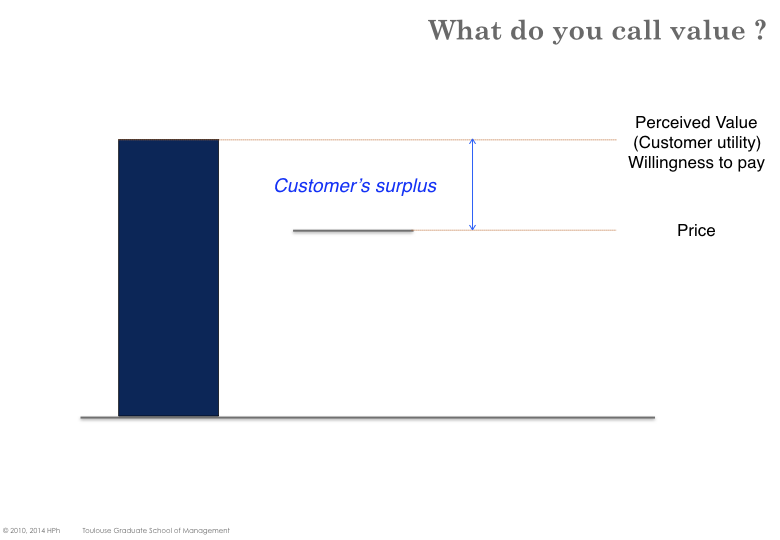

What is Customer Value

A Value proposition is the description of the offer (product or service) made by a company to its customer and why the offer is attractive to customers. But, before looking at the characteristics of Value Proposition let’s pause and first consider what is meant by Value.

Customer Value

Customer value is also named usefulness or utility by economists. In economy, utility doesn’t convey any ethical, moral, religious or political connotation but only reflects preferences from economic agents. V. Pareto proposed to use the word ophelimity instead of utility. However the former was already too well established in economics literature.

For customers, Value yields from the perceived ability of a good or service to satisfy a need.

The willingness to pay is the maximum price a customer is ready to pay to acquire a given good (product or service). This is the amount for which the customer is (theoretically) indifferent between keeping her/his money or obtaining the good. At a higher price, the customer would rather keep the money (which is worth more than the good’s utility for that customer). If offered at a price which s strictly inferior to the willingness to pay, then the customer can consider a commercial transaction. The difference between the transaction price and the perceived value is named customer’s surplus. If customers are rational, the surplus must always be positive.

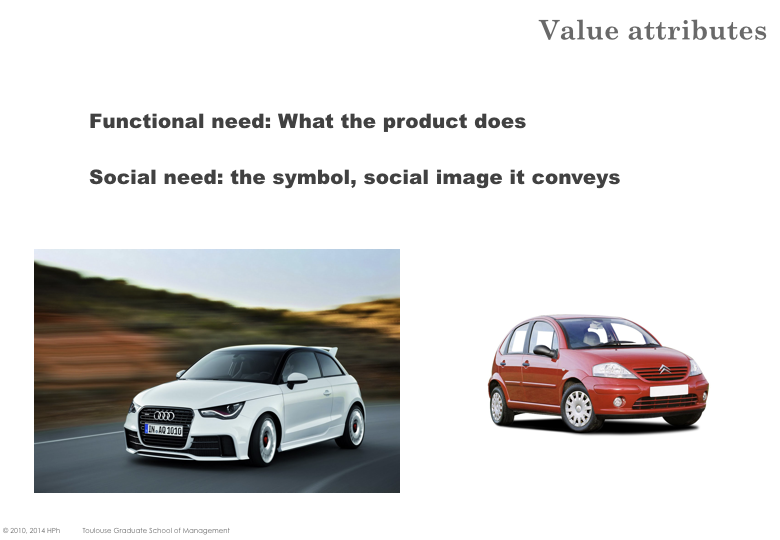

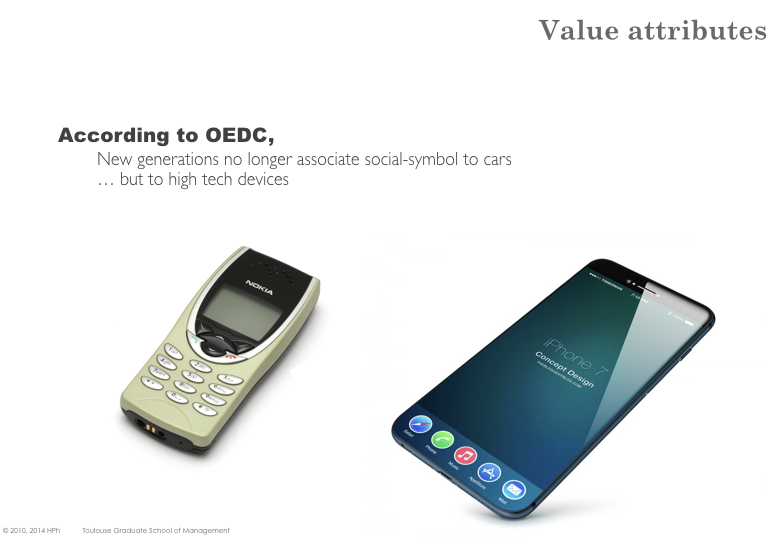

Practical vs. Demonstrative dimensions of Value

Human needs are infinite and insatiable. Psychologists define a need as a gap that triggers some action. Several classification of human needs have been established (e.g. Maslow’s pyramid which identifies the need for security, membership, self-esteem, …). However, by and large there are only two fundamental types of needs:

functional needs (including basic needs: breathing, feeding, breeding)

social needs (which may be contradictory: resemble others, assimilate to the group but at the same type differentiate oneself from the crowd, be recognized as individuals).

A product or service always aims at satisfying a need. However most needs combine basic needs (functional need) with social needs and are met by socially significant forms (to have dinner at a fancy restaurant vs. eating). The value of a proposition must always be considered from the perspective of the customer(s). Value derives from utilitarian aspects but also from more peripheral elements related to the context of consumption, use and/or purchase which represent more subjective but nevertheless real and often substantive sources of satisfaction.

Value can for instance be attributed - see ( [Aurier] ) for a more detailed ontology - to the functional aspects (performance in terms of tangible, concrete rendered service), knowledge acquisition (education, cultural products, museum), emotional stimulation (entertainment, personal experience), self expression and establishment of a social bond.

Products & services therefore also encompass consuming signs (willingness to display a status, need for control, need for security). A value proposition has therefore two dimensions: a practical / functional dimension and a demonstrative / social dimension.

### Value Propositions compete with a broad set of substitutes Customers, through their behaviors and consumption logic, determine which companies are actually competing. Hence it is crucial not to start any strategic analysis with an a priori definition of strategic groups. By contrast, it is key to look at actual trade-offs made by customers and understand how their choices depends on the emotional value and usefulness they perceive in products.

Firms compete with each other in product markets to the extent that they may attract the same customer and serve similar needs.

As stressed by Peteraf and Bergen ( [Peteraf03] ) > „The identification of the originality of the offer in terms of value delivered to the customer is at the heart of the definition of a business model specific to a company. The identification of rivals in the satisfaction of the same need of the customer is an essential task for the configuration of an innovative business model.”

Potential substitutes and new entrants are often the highest competitive threats but also the most challenging to foresee. They are usually the ones who cause the break in the sector and can profoundly change established rules of the game.

Consumption Context Can also Matter

Value Proposition attributes are not limited to the functional & social aspects of the product or the service. Indeed, sometimes the context in which the pro- duct/service is consumed also significantly matters.

Dawar ( [Dawar03] ) stresses that on a hot day, consumers are ready to pay 7-fold more for a cold soda. The perceived value of the product is therefore influenced by the circumstances. Dawar goes on step further an claims that the way the product is channeled to customers (the place in mix-marketing terms) can also seriously affect the perceived value.

Customers don’t always know in advance what they (might) value

While Marketing hasgrown the concept of focus groups (where people are asked about their perceptions, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes towards a product, or service) many innovators are considering that consumers are not always capable of anticipating their needs.

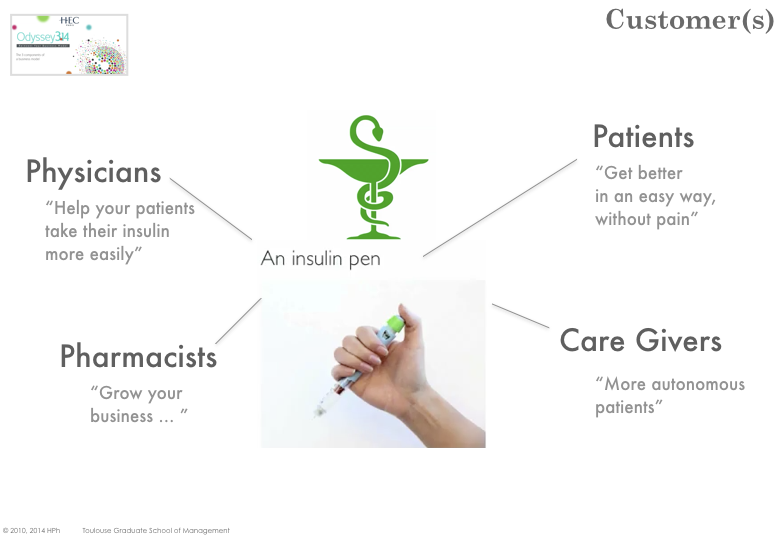

Customers

When dealing with Business Models, the word Customer must be understood in its broadest sense. Theoretically, any stakeholder who interacts with the product or plays a role in the purchase decision, should be considered a Customer.

In their MOOC ( [Lehmann-Ortega15] ) L. Lehmannn-Ortega and Hélène Musikas develop the example of an insulin pen that generates value for patients (who use it) for doctors (who prescribe it), for pharmacists (who sell it) for Care givers (health care staff, family members, who can spend more time with patients and less on technical aspects). The list could be extended as well to Health Care Insurance companies and the Health Care Authorities.

Customer roles will typically include:

Users - or consumers - will gain benefit from actually using the product or service. For instance in the Air Transport system, passengers are usually the users of aircraft (although pilots, cabin crew and mechanics would as well be a different kind of users).

Recommenders - can advise or suggest specific products or services. For some products (e.g. medical treatment prescription) recommenders can select the product for users.

Opinion leaders - don’t necessarily interact directly with users or decision-makers, but their opinion can significantly influence the decision to buy or not to buy. With the advent of the social web, any potential user can as well become an opinion leader / influencer for other customers.

Buyers - paying customers will handle the economic transaction and will usually pay for the product or service.

Decision-Makers - select the product or service. For B2C (Business to Consumers) businesses, the Decision Maker is often also the Buyer and the User. This is usually not the case for B2B (Business to Business) businesses.

What Job do you hire the product for ?

Clayton Christensen ( [Christensen07] ) proposes a specific framework to help identify customer expectations and competitive arenas. In the original article and also in many videos available on the Internet, the concept is illustrated with the story of a fast-food restaurant that was seeking to improve the sales of its milkshake sales.

The restaurant had done a lot of data crunching and segmented its market both by product (milkshakes) and by demographics (attributes of milkshake drinkers). They also had run focus groups where they asked to representative customers what they would fancy. Despite all these quantitative and qualitative data gathering, the restaurant hadn’t substantially improved its sales.

The restaurant then enlisted a team of researchers from Clayton Christensen’s lab. They approached the topic by raising the question:

“What job arises in people’s life that causes them to come to this restaurant to hire a milkshake?”.

On the first day they stood in the restaurant for several hours, recording very detailed facts about customers: were they coming alone or in group, what time did they get to the restaurant, did they buy other food, did they eat it in the restaurant or drive off with it, etc. It turned out that half of the milkshakes were sold before 8 am, to people always alone, it was the only thing they bought and they drove off with it immediately.

On the second day the researchers interviewed these specific customers and discovered that they all had a lot and boring drive to work and they had to do something to keep the commuting interesting.

The restaurant was in fact facing two categories of customers and was therefore playing in two distinct competitive arenas. In the morning it was facing commuters and in the afternoon parents with Children. The two categories of customers had very different expectations and were ”hiring milkshakes” for completely different jobs.

We often wrongly assume that we know right away in which industry we compete. However, the competitive arena(s) in which you are competing can only be unveiled by really scrutinizing the job the customer is hiring you to do.

Once you have clearly figured out what jobs customers are hiring you to do, you can more easily identify:

who your customers and buyers are i.e. who can benefit from the job your product can do

who your suppliers should be,

who your competitors are or might be, i.e. who else (can) do identical job,

who might be potential entrants / substitutes, i.e. who may do similar jobs,

Value Proposition Design Framework

The value proposition design framework ( [Osterwalder12] ) aims at defining in a more structured way the most adequate value proposition. Please note that this section is deeply inspired from the web site Business Model Alchemist .

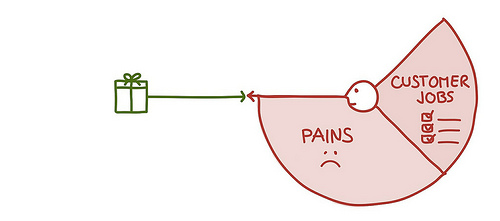

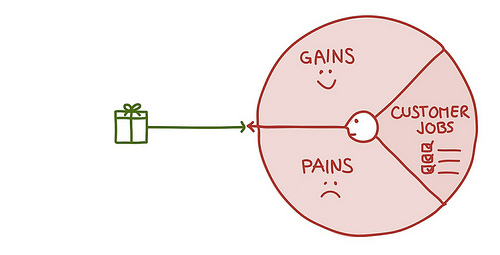

The first step consists in identifying customers or potential customers.

From there, one should seek to identify what the targeted customers are trying to achieve, what are the problem they are trying to solve (aka customer’s jobs), the needs they are trying to satisfy. It is noteworthy that needs may not be only functional (i.e. complete a specific task) but can also be social (e.g. status, power, belonging) and emotional (e.g. aesthetics, security, …).

Once needs are clarified, one should consider all potential sources of pains (i.e. negative emotions, frustrations, costs, risks, inconvenience, discomfort, under-performance) that are experienced by the customers before, during and after getting their need satisfied.

Likewise, one should identify all the features and benefits that customers expect, desire or would be thrilled by. Again this is not limited to functional aspects but may cover as well social gains, positive emotions, cost-time-effort savings. Existing products and solutions are likely to already address some aspects (but probably not all or not for all customers).

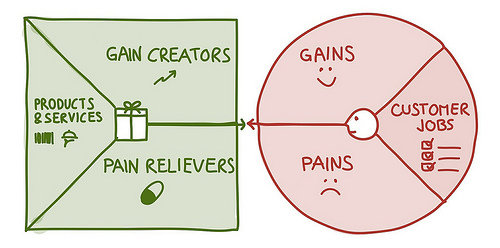

Design a Value proposition

The value proposition is the response to a customer need. It may encompass product and services (tangible good, one-to-one customer facing service, on-line interaction, branding and other intangible aspects, financing services, etc).

Once the pains are clearly identified, it is easier to check how the value proposition alleviate these pains and how much pains are eliminated. Likewise, it is easy to underline which customer expectations are addressed by the value proposition and what specific benefit (possibly compared to what competitors do) is brought.

C. Christensen ( [Christensen08] ) stresses four aspects that should be considered in priority to unveil untapped market spaces:

Wealth barriers sometimes customers don’t have enough revenues to afford existing value propositions. When Tata looked at creating a new car for Indian domestic market, they knew they had to compete with US$ 2500 scooters. The size of the Indian market allows for rebalancing the profit equation through volume.

Skill barriers customers don’t always have the knowledge, technical background or competence to use mainstream solutions. This is particularly true in Business to Business segments where the solutions targeted at SMEs are different from the solutions used by large corporations.

Time barriers mail-order selling and more recently internet-based shopping have grown as consumers get aware of the time required to shop in physical stores in city centers or shopping malls.

Access barriers some form of asymmetry of information may make the service and / or product difficult to find and access. For example, independent consultants are usually barely visible outside their close network. A bypass strategy can consist in relying upon a business ecosystem that is sufficient to leverage the value proposition.

On their website, BCG stresses that

„In the past 50 years, the average business model lifespan has fallen from about 15 years to less than 5. Business model innovation is thus no longer one of many ways to gain a competitive edge, but it is a necessary core capability to respond to – and capitalize on – a changing world.”

It is therefore crucial to clearly identify all the stakeholders (potential customers) and understand their motivations to accept or reject a value proposition.

Many Business Model innovations draw from the decoupling of the various customer roles (i.e. the using customers vs the paying customers).

Value Price Positioning

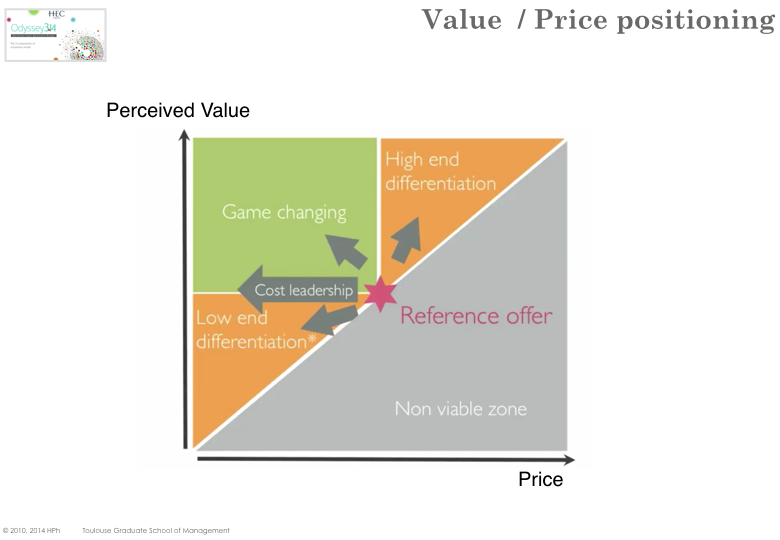

For a given type of needs there might exist many different value propositions. A common way of comparison is to draw them along two axes: customer perceived value and price. While many combinations are possible, five distinct areas can be spotted.

Reference Offer - when a market is mature enough there will be a value proposition (or range of value propositions) that is considered the reference offer both for its price and its (perceived) value. Any other proposition will be compared against this reference point.

In a nascent market, the reference offer is usually the first entrant. In case of market shake-up the reference can be the products that are being substituted. Sometimes, the reference offer only exists in customers’ mind (e.g. as an average offer).Non Viable zone - any value proposition that would yield less value than the reference offer but at a higher price would obviously be disregarded by customers (who would accept to pay more for less?). Likewise, at any requested price, any offer that doesn’t bring enough value (relatively to other VPs) is considered as non viable.

Price discount a first differentiating option is to offer similar value (compared to the reference offer) at lower price. This option to be viable for the firm requires that the firm can deliver the same value for less cost, hence the name of Cost Leadership. When several players are capable of delivering this option it usually becomes the new reference offer (and the former reference point becomes non viable).

Low-end differentiation less value is offered at a discount compared to the reference offer. Such value propositions would not appeal to all customers but it can be viable if some customers are ready to trade product attributes against a price discount. Low Cost Carriers in Aviation are typically offering less services at a cheaper price.

High-end differentiation this is the opposite approach. New features are included to the product for a higher price. Building on the same example a first class airline ticket offer more comfort but is significantly more expensive than economic class.

Game Changing is a position that provides both a price discount and value increase (at least for some customer segments). When a game changing value proposition is introduced, it is likely to supplant the existing reference offer and quickly become the new reference point.

Bowman’s Strategy Clock

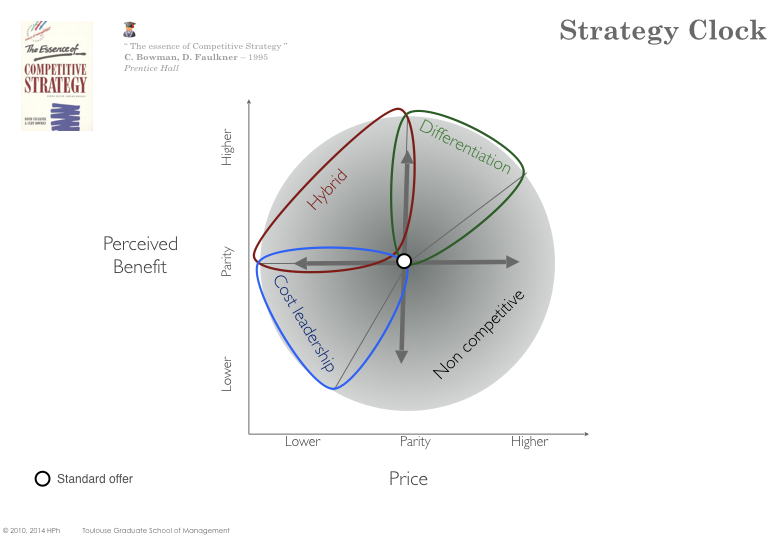

The Strategy Clock ( [Bowman97] ) is an other model that explores the various value/price positions.

In its simplest version, it stresses tree areas: i) cost leadership strategies that allows for different combinations of lower price at lower perceived value, ii) differentiation strategies with above average value proposition at a premium, iii) non-competitive strategies that are non-viable and iv) hybrid strategies with both above average features and cheaper price.

It is noteworthy that with this model, differentiation means more value.

At 12 o’clock - Differentiation without any price premium - corresponds to a highly differentiated product/service (highest perceived value) that is offered at parity price. This position can usually not be sustained in the long run (especially not if higher costs are implied) but still can be chosen as a market entry strategy to quickly gain market shares (more features at no extra cost)

At one o’clock - Differentiation with price premium - represents the typical differentiation strategy where a higher perceived value translates into higher prices.

At 2 o’clock - Some differentiation with high premium - this is likely to soon become some sort of focussed differentiation (i.e. targeting a customer segment with specific customer needs / addressing an area with little competition). Although the perceived value by the average customer is close to parity, the specifically targeted segment see far more value (e.g. there is one feature that is of no use for the average customer but key for the targeted customer) and is therefore willing to pay more.

3 o’clock to 6 o’clock non-viable positions

7 o’clock - Low price with lower value - This is the typical no-frills strategy (e.g. low cost airlines) where a company downgrades the product attributes, hence both the perceived value and production costs.

9 o’clock - Low price at product parity - this generic cost leadership strategy combines lower price and reasonable perceived value (compared to the average competitor). In this position a company would drive its costs to the bare minimum and balance very low margins with high volume. A well-installed cost leader can sustain this approach. However there is a risk that prices become unstable and that a price war breaks out, which would i) benefit consumers only, ii) destroy company value and iii) usually lead to industry consolidation

10 - 11 o’clock - Lower price and higher value - This zone allows for major changes: strategies that both involve low price and some differentiation. The perceived value (at least for some product attributes and some customer groups) is above average while price are still below average. A hybrid strategy can be chosen by a company wishing to enter a new market (product segment, export) or to speed-up market penetration and create customer lock-in effect (e.g. proprietary standard). Some companies can sustain hybrid strategies over a long period of time. Furniture store IKEA, for instance, combines economy of scale, no frills (DIY, no delivery, etc) and differentiated design.